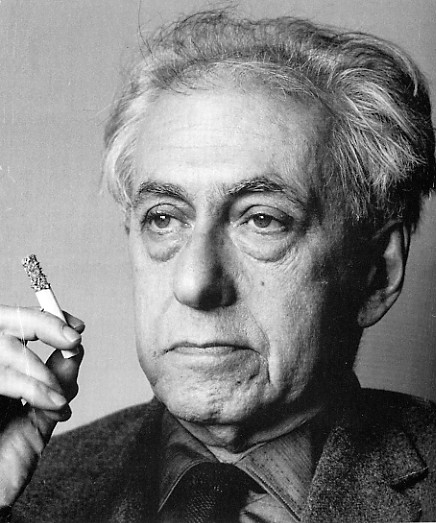

Tribute to

Ilya Ehrenburg

by Aleksandr Tvardovsky

presented by

Tribute to

Ilya Ehrenburg

by Aleksandr Tvardovsky

presented by

Veteran Soviet Writer Ilya Ehrenburg passed away on 31 August 1967, at 76 years of age. This tribute, by poet and chief editor Aleksandr Tvardovsky, appeared in the September 1967 issue of Novy Mir.

This is one of those losses which suddenly reveals the significance of the deceased to be of far greater scope than was imagined during his lifetime.

Ilya Ehrenburg was not bypassed by praise, by the recognition of millions of readers--fellow countrymen and foreign friends alike. The literary and social activity of this renowned writer was acknowledged with many awards, from the International Lenin Prize for Strengthening Peace Among Peoples to the French Legion d'Honneur.

A writer-humanist, he was among those who, together with Gorky, recognized the danger that fascism posed to peace, culture, and democracy. An indefatigable fighter against all ideologies of barbarism and obscurantism, Ehrenburg, even before the Great Patriotic War, had won the recognition and respect of wide circles of readers not only in his homeland but also among the leaders of the world's intelligentsia. His word, hardened by experience during the struggle for republican Spain, began to resound with extraordinary force when it was turned to the defenders of his native Soviet soil. They cherished his words on the bitter path of retreat as well as on the difficult path of victory from Stalingrad to Berlin. With good reason, even the enemy took note of this voice. You just have to recall how the Hitlerites in their leaflets threatened any Soviet war writer with furious rage: "...just you wait, Ilya."

In the post-war years, Ehrenburg turned all his mature talent as an artist and publicist and his far-reaching connections with leading members of European society to the task of establishing peace for the whole world; his voice sounded with unrelenting passion and conviction. The name of this fighting writer, this champion of the ideas of humanism and internationalism, was deservedly renowned throughout the entire world.

Ehrenburg's fate as a writer can be called fortunate. It happens only rarely that a writer in his declining years creates his most significant book, as if in summary of his entire creative life. One can have varying opinions about various pages in People. Years. Life.*, but no one can deny the great significance of this work, not only in terms of Ehrenburg's creative work, but also in relation to all of our literature in its new stage of development in the years following the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

First among literary men his age, Ilya Grigorevich Ehrenburg addressed contemporaries and future generations with this story "about time and himself", a confession of his life intertwined in one way or another with the great and complicated half-century history of our revolution. He boldly stepped out from behind the cover of conventions, exaggerations, and assumptions that are characteristic of the generally accepted literary form of fiction. In this book he found a breadth of content and a natural ease that is highly valued by the reader. We have had nothing comparable up to this point.

When his book appeared on the pages of Novy Mir, some of Ehrenburg's critics advised him to recall in his memoirs those things which he could not remember and to forget those things which he could not forget; but the writer remained true to himself. And despite the inevitable drawbacks of the "subjective genre" of memoirs, the novelist, publicist, aesthete, and poet Ilya Ehrenburg, in my view, as a result of the confluence of the various aspects of his literary talent and life experience, achieved a great creative victory precisely in this genre, engaging the reader with the sincerity and spontaneity of a direct witness to the past. This book, which has already circled the world in many translations, is undoubtedly assured a firm longevity.

From our vantage point of today, surveying the great and complicated path of this writer, we see that he was always at the forefront, at the most burning edges of contemporary society. He never sought a quiet and peaceful life in art, and he bravely endured the frequently thoughtless and unjust reproofs and reproaches of critics.

Ehrenburg had and continues to have a large groups of readers, who can never remain indifferent to his words. To judge by the letters addressed to the editors of Novy Mir, Ehrenburg's mail from readers was extensive and varied. There are expressions of gratitude, questions, good wishes, and critical comments-- that incorruptible and organic contact between the writer and those for whom he writes and without whom literature loses all sense as a great social phenomenon.

Ilya Grigorevich could not complain about a lack of attention from professional critics. For his entire life, they took him to task, lectured him, and worked him over; but they also praised him and extolled him beyond measure. It was simply impossible to keep silent about him.

Yet all the same, today, when his voice has fallen silent, we see the significance and place of Ilya Ehrenburg in a new and expanding sense, and we are evaluating anew the entire literary life of our prominent colleague. But the point is not to blame ourselves for the fact that, possibly, we did not adequately value his presence in our ranks.

It is not without good reason that people say that, in this life, it is better to receive too little than too much. As concerns literary fates, receiving too little during life is not an unusual matter; but it is also not a detriment for a writer, whose significance is not limited to his physical presence on the earth. Sooner or later, everything finds its proper place on the shelves.

*People. Years. Life. Ehrenburg's memoirs, originally published in Novy Mir.

See also:

The Thaw. Summary of Ehrenburg's 1954 novel which gave its name to an entire era of Soviet history.

The Storm. Excerpt from Ehrenburg's 1948 novel about World War II, with action taking place in both the Soviet Union and France.

Biography of Ilya Ehrenburg.

Return to: SovLit.net

Address all correspondence to: editor@sovlit.net

© 2012 SovLit.net All rights reserved.