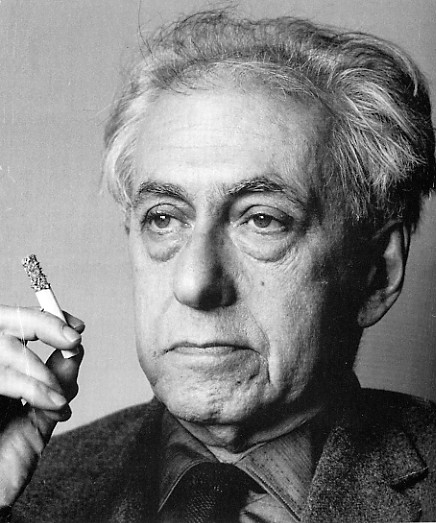

Ehrenburg, Ilya Grigorevich. Born on 26 January (14 Jan, Old Style) 1891 in Kiev, the son of an

engineer. Originally given the name Eliyahu, Ilya had three older sisters. His father had no interest in Jewish ritual,

while

his mother continued to observe religious customs. On this matter, Ilya followed his father's example, and never learned

Yiddish or Hebrew.

Ehrenburg, Ilya Grigorevich. Born on 26 January (14 Jan, Old Style) 1891 in Kiev, the son of an

engineer. Originally given the name Eliyahu, Ilya had three older sisters. His father had no interest in Jewish ritual,

while

his mother continued to observe religious customs. On this matter, Ilya followed his father's example, and never learned

Yiddish or Hebrew. As a boy, Ilya was rather undisciplined and, by his own admission, "it was only chance that I did not become a juvenile delinquent." In 1895 the family moved to Moscow where his father was appointed manager of a major brewery. The Moscow home of Lev Tolstoy adjoined the brewery, and young Ilya would often see the elder writer strolling about. Ilya enjoyed a relatively privileged lifestyle and attended the First Gymnasium where he met and became friends with Nikolai Bakhunin, who was also a student. Ilya got involved in politics and was in the crowds erecting barricades during the Revolution of 1905. In 1906 both Ehrenburg and Bukharin joined the Bolshevik organization. Ehrenburg and Bukharin edited an underground journal, spoke at meetings, collected funds, and organized a strike at a wallpaper factory. Ehrenburg also worked to establish a Bolshevik cell in a soldiers' barracks. In January 1908, the 17-year-old Ehrenburg was arrested. The police were not gentle and broke several of his teeth. After five months in prison, Ehrenburg was allowed out for medical reasons. However, instead of staying out of trouble, he resumed his illegal political activities. His father intervened at this point, paying a deposit of 500 rubles to get Ilya permission to go abroad for medical treatment. Ilya's mother wanted him to go to Germany and resume his studies, but on 7 December 1908, the young Ehrenburg arrived in Paris because, as he wrote in 1960, that's where Lenin was. Ehrenburg immediately attended a meeting where Lenin spoke. As Ehrenburg recalled years later: He [Lenin] spoke very calmly, without melodrama and with a slightly ironical smile. ... I was fascinated by his head. ... It made me think not of anatomy, but of architecture.Eager to hear the impressions of a young person fresh from Russian, Lenin invited Ehrenburg for a private dinner and conversation. Soon, however, Ehrenburg's interest in politics began to wane, and he took to writing poetry. Not ready to give up politics entirely, he took the recommendation of Lev Kamenev to go to Vienna and work with Lev Trotsky. In Vienna, Ehrenburg helped prepare copies of Pravda to be smuggled into Russia. He had conversations with Trotsky about art. He found Trotsky to be dogmatic and intolerant, calling the poets Ehrenburg admired "decadents" and "the product of political reaction." This attitude depressed Ehrenburg, so he returned to Paris where he decided to renounce politics and devote himself to literature. With the help of poet Liza Polonskaya, Ehrenburg produced a few magazines lampooning most of the revolutionary leaders, including Lenin, who, in one caricature, was labeled a "chief janitor" (starshii dvornik). Lenin saw and was outraged by the lampoon. Living on an allowance sent by his father, Ehrenburg spent most of his time reading and writing in the cafes. He developed a fascination for Catholicism and considered converting and entering a Benedictine monastery. Near the end of 1909, Ehrenburg met and fell in love with Katya Schmidt, an emigree from St. Petersburg. On 25 March 1911, she gave birth to Ehrenburg's only child, Irina. Ehrenburg was not prepared for the responsibilities of being a husband and father and he never married Katya. In 1910 Ehrenburg came up with enough money to publishe his first poetry collection, Verses (Stikhi). It contained poems on themes of Catholicism and the Middle Ages. The prominent Symbolist poet Valery Briusov found the work "elegant" and "beautiful. He wrote: Among our young poets, Ehrenburg is second only to Gumilev in his ability to construct verses and derive effect from rhyme and the combination of sounds.Gumilev, however, was unimpressed, stating that all he found in Ehrenburg's work was "ungrammatical and unpleasant snobbism." Ehrenburg's second volume of poetry was published in 1911. It again contained Catholic poems, but also "To the Jewish People", a poem voicing despair over the historical plight of the Jews. This volume was more to Gumilev's liking, and he wrote: I. Ehrenburg has made great progress from the time of his first book's appearance. . . . He has passed from the ranks of imitators into the ranks of apprentices and, even, sometimes, steps forth on the path of independent creativity.During this time, Ehrenburg spent most of his time at the cafe Rotonde, whose clientel also included Picasso, Apollinaire, Diego Rivera, Juan Gris, Jean Cocteau, Modigliana, and Marc Chagall. In 1912, Ehrenburg, an official fugitive from Russian justice, applied for a commutation of his sentence, knowing that the Tsar was likely to grant a broad amnesty in connection with the 100th anniversary of Romanov rule. The request was denied. In 1913, Ehrenburg helped edit two issues of the journal Helios, in which he wrote glowingly about the verse of Marina Tsvetaeva. In 1914, he published an anthology of his own translations of French poets, including Verlaine, Rimbaud, and Apollinaire. When World War I broke out, Ehrenburg tried to enlist in the French army, but he was rejected as being too gaunt. Instead, Ehrenburg wound up working as a war correspondent for the Russian papers Utro Rossii and Birzhoviye Vedomosti. His reporting was intelligent, skeptical, and fair. His coverage of the French army's shameless use of bewildered Senegalese troops in the most exposed positions so infuriated the French government, that Ehrenburg was almost expelled from the country. The war took a toll on Ehrenburg, and he suffered a nervous breakdown. He began to yearn for his homeland, and after the February Revolution, he set back for Russia. He arrived in Petrograd just after the July days. His political leanings at the time were in favor of Kerensky, not the Bolsheviks. He moved on to Moscow where he met the October Revolution by cowering in his room as street fighting raged outside his window. In early 1918, Ehrenburg published a collection of verse entitled A Prayer for Russia (Molitva o Rossy). One work in this collection, "Judgment Day", makes Ehrenburg's hostility to the Bolsheviks apparent. It features Red soldiers stopping to rape a woman as they storm the Winter Palace. Mayakovsky denounced the collection as "tiresome prose printed in verses" and Ehrenburg as "a frightened intellectual". Later (in 1921) Ehrenburg himself dismissed the collection as "artistically weak and ideologically impotent". Throughout 1918 Ehrenburg wrote anti-Bolshevik articles, calling Lenin "a stocky bald man" who resembles "a good-natured burgher." He called Kamenev and Zinoviev "high priests" who "prayed to the god Lenin". In 1919, things got too hot in Moscow for Ehrenburg, so he moved to his home town of Kiev. He met and associated with various writers including Andrei Sobol and Osip Mandelshtam. In August, Ehrenburg married a distant cousin named Lyubov Mikhailovna Kozintseva. He took a job as head of the aesthetic education of juvenile delinquents and seems to have done an admirable job. In September 1919, the Whites took control of Kiev, and Ehrenburg resumed publishing hate-filled anti-Bolshevik articles, calling Lenin's revolution a "drunken orgy", the Bolsheviks "rapists and conquerors". This attitude, however, did not appease the fiercely anti-Semitic Whites. They came looking for the Jew Ehrenburg at a newspaper office once, but the printers hid him. So Ehrenburg fled to the Crimea with his wife and his mistress and from there returned to Moscow. Two weeks after his arrival in Moscow, Ehrenburg was arrested and accused of being an agent of Wrangel. Four days later, however, he was released, probably through the intervention of Bukharin. Resuming his literary life, Ehrenburg hob-nobbed with the usual suspects--Andrei Bely, Boris Pasternak, Sergei Esenin, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam, etc., etc. He was just barely surviving by doing readings and literary reviews. Then he found a real job supervising the nation's children's theaters for the Ministry of Education. His direct superior was Vsevolod Meyerhold. Still, life was hard and, once again with Bukharin's help, Ehrenburg was one of the first Soviet intellectuals to be granted a passport to travel abroad. Forced to leave his mistress behind this time, Ehrenburg took his wife and set off for Paris in March 1921. But in 1921, after only two weeks in the French capital, the French police grabbed Ehrenburg and expelled from the country, never giving a reason. Ehrenburg wound up in Belgium where he sat down and in 28 days turned out his first novel The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenita and His Disciples (Neobychainiye Pokhozhdeniye Khulio Khurenito). In the novel, the mysterious Mexican Julio Jurenito meets up with a fictional Ilya Ehrenburg and several other disciples, who follow him on a quest to disrupt Europe, undermining its myths and complacent assumptions about religion, politics, love, marriage, art, socialism, and the rules of war. The Pope is lampooned, as it the eternal internal bickering among socialist factions. Eerily, the Nazi Final Solution is presaged as Julio sends out invitations to the extermination of the Jewish tribe. In Moscow, Jurenito meets with a Bolshevik leader obviously meant to represent Lenin. This fictional Lenin shows himself to be ruthless, vowing to exterminate all enemies. Julio Jurenito created an immediate sensation, winning universal praise, even from Pravda. Bukharin wrote an introduction to the Soviet edition of the novel, calling it "a most fascinating satire" that exposed "a number of comic and replusive sides to life under all regimes. Evgeny Zamyatia noted in particular Ehrenburg's use of irony, calling it a "European weapon" seldom used by Russians. He applauded Ehrenburg for ridiculing all targets equally, and readily accepted Ehrenburg into the brotherhood of heretics. Of Ehrenburg, Zamyatin wrote: He is, of course, a real heretic (and therefore--a revolutionary). A genuine heretic has the same virtue as dynamite: the explosion (creative) takes the line of most resistance.In October 1921, Ehrenburg moved to Berlin, where the tempo of his literary output increased. By 1923 he had produced three more novels. In Trust, D.E., American millionaires finance a plan to destroy Europe with viruses and poison gas. The Love of Jeanne Ney is the story of a love affair between a young, respectable French bourgeois woman and a Russian Communist, who is sent to France on a subversive mission. He is arrested on a murder charge and the only way to prove his innocence to to reveal his true mission. He remains heroically silent and is sentenced to death. Jeanne sacrifices her honor in a vain attempt to save her lover. The Life and Death of Nikolai Kurbov (Zhizn i Gibel Nikolaya Kurbova) is about a dedicated member of the Cheka who becomes disallusioned when the NEP is announced, and he ends up killing himself. The novels were quite popular, but did have their critics. Writing in the journal Na Postu ("On Guard"), Boris Volin denounced Nikolai Kurbov as: ...nauseating literature that distorts revolutionary reality, libels, exaggerates facts and types, and without stop and without a twitch of conscience slanders, slanders, slanders the revolution, revolutionaries, Communists, and the party.In early 1924, Ehrenburg spent several months touring the Soviet Union, giving lectures and readings. He then returned to Paris and finished The Grabber (Rvach), which Veniamin Kaverin was to call Ehrenburg's finest novel. It is the story of a Social-Revolutionary. When his party's revolt fails in 1918, he flees to Kiev. He survives the Civil War and eventually makes his way back to Moscow as the NEP is in full swing. But he no longer understands society's rules, gets arrested because of links to a currency speculator, and commits suicide in jail. On Portochnoi Lane (aka "A Street In Moscow") (V Portochnoi Pereulke, 1927) is a graphic and often sordid account of daily life in a Moscow working class area during the mid-1920s, as characters come to terms with changes brought by the Revolution. That same year, Ehrenburg published White Coal, or the Tears of Werther, a collection of essays on European culture and society. Ehrenburg followed this with The Stormy Life of Lasik Roitschwantz (Burnaya Zhizn Lazika Roitshvantsa). The hero of this novel is a simple, good-natured Jew from Belorussia who wanders to Moscow, Warsaw, Germany, France, England and Palestine, suffering beatings, jailings, and indignities of all sorts wherever he goes. Official Moscow was not pleased with this book, and even Ehrenburg's friend Bukharin called it "one-sided literary vomit". In 1928, he published Conspiracy of Equals (Zagovor Ravnykh), a historical novel concerning the Babeuf movement in Revolutionary France, which rejected terror and advocated an egalitarian democracy. Stalin did not like this work, dismissing it as "pulp literature" suitable for "a real bourgeois chamber theater." In the face of the increasing criticism from Moscow, Ehrenburg gradually began to shift his writings into a more openly pro-Soviet direction. He wrote about European peasants, blasted Poland's authoritarian rule and France's racist colonialism. He undertook a series of stories and novels exposing the greed of noted wealthy entrepreneurs. The Life of the Automobile focused on Andre Citroen, Pierpont Morgan, and Henry Ford. The Shoe King attacked Tomas Bata, a Czech footwear capitalist. Factory of Dreams takes on Hollywood, George Eastman, and the Kodak camera. The Single Front takes as its target Ior Kreuger, the Swedish Match King. The capitalists were not amused. Bata sued Ehrenburg, and Kreuger opened a public relations war against the writer. Moscow wasn't particularly thrilled either, however. While these books exposed abused of capitalism, they failed to suggest communist as the solution to these ills. The 1931 edition of the Small Soviet Encyclopedia described Ehrenburg thusly: He ridicules Western capitalism and the bourgeoisie with genuine wit. But he does not believe in communism or the proletariat's creative strength.In 1931 Ehrenburg visited Germany twice. The rise of Nazism which he saw there gravely disturbed him. It seemed to him that war was inevitable and he could no longer remain an uncommitted skeptic because, as he wrote later, "Between us and the Fascits there was not even a narrow strip of no-man's land." In 1932, Ehrenburg became a reporter for Izvestiya, covering the trial of a deranged Russian emigre who had assassinated the French President. In addition, hHis articles were persistent and clear in calling attention to the danger of the rise of fascism. Later that year, Ehrenburg returned to the Soviet Union. He spent weeks in Siberia, touring construction sites in Sverdlovsk, Tomsk, and Kuznetsk. Upon his return to Paris, Ehrenburg penned The Second Day (Den Vtoroi), sometimes translated as "Out of Chaos". It is a day-to-day account of the harsh conditions of life and heroic efforts of workers to overcome nature's resistance as they built a blast furnace in Kuznetsk. In the novel, a weak dreamer tries to fit in with the more dedicated workers but fails. He becomes complicit in an act of vandalism. Ashamed of his own spiritual bankruptcy, he commits suicide. This work was Ehrenburg's attempt to reestablish himself politically in the Soviet Union. At first, publication was rejected. But Ehrenburg sent copies to Stalin and other members of the Politburo. He got lucky, and publication was approved. Also in 1932 Ehrenburg also produced the novel Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (Moskva Slezam ne Verit) about the difficulties of a Russian artist who has the opportunity to study in Paris. The artist is attacked by a critic at home who denounces his work as degenerate and bourgeois. In this work, Ehrenburg makes the point of comparing western capitalist society is to a lavatory in a fifth-rate Paris hotel. In 1934, Ehrenburg convinced French writer Andre Malraux to accompany him back to the Soviet Union to attend the first Soviet Writers' Congress. Ehrenburg was on the presidium of the Congress and chaired several of its sessions. In his main speech to the Congress, he defended the need for books that appealed only to "the intelligentsia and an elite among the workers" and may not be understandable to the broad masses. He spoke in praise of Isaak Babel and Boris Pasternak and added his voice to the pleas for greater tolerance of artistic literature. In 1934 Ehrenburg also completed the novel Without Taking Breath (Ne Perevodya Dikhaniya), which centers on heroic efforts to develop a modern timber industry in the far north. The novel also describes the wholesale destruction of wooden churches from the 17th and 18th centuries and the neglect of tradtional Russian lace-making in the region. Ehrenburg was a participant and one of the principal organizers of the International Writers' Congress in Defense of Culture, which began its work on 21 June 1935. The goal of the congress was to organize a broad anti-fascist coalition of writers from a wide range of perspectives--liberal, socialist, communist, Christian, and Surrealist. In fall of 1935, Ehrenburg made a quick trip back to Moscow. While there, he gave speeches and wrote articles in praise of Pasternak, Babel, Meyerhold, Dovzhenko, and the independence of art. This resulted in some criticism of Ehrenburg. Vera Inber, for example, rebuked him for implying that only Pasternak had a conscience among Soviet poets. When the Spanish Civil War broke out in summer 1936, Ehrenburg immediately dashed to Spain to report on the war, disobeying instructions from Izvestiya, which wanted him to stay put in Paris. His reporting was intelligent and passionate, maintaining a constant drumbeat of anti-Fascism. While in Spain, Ehrenburg also got to meet yet another literary luminary--Ernest Hemingway. By 1937, he put together a book of sketches on the war entitled What A Man Needs. In December 1937, Ehrenburg had a really stupid idea: he went to Moscow for a short vacation at the height of the terror campaign. His friends back in Moscow couldn't believe how foolhardy he was to return at a time when writers were being arrested right and left. He expected to return to Spain after two weeks, but authorities told him this would not be possible. On the orders of Stalin, he was given a ticket to attend the trial of his old friend Nikolai Bukharin. Izvestia wanted him to write an article on the trial, but Ehrenburg adamately refused. Unknown to Ehrenburg at the time, Karl Radek, one of the Bukharin's co-defendants, had revealed under "interrogation" that Ehrenburg had been present while Radek and Bukharin were plotting their coup. Fearful and tired of waiting, Ehrenburg sent an appeal to Stalin, asking to be sent back to Spain. The request was refused. Knowing that he was being extremely foolhardy, Ehrenburg decided to "play the lottery" and sent a second appeal to Stalin which--no one knows why--was granted this time. Back in Europe, Ehrenburg continued writing dispatches from Spain and France. Then he suffered a severe shock in August 1939 with the announcement of the Hitler-Stalin pact. He was so shaken that for eight months he could only take in liquids and chew on herbs and vegetables. He lost 40 pounds. In Moscow, Ehrenburg's reputation suffered. HIs dacha in Peredelkino was handed over to Valentin Kataev. Following the German invasion of Belgium in May 1940, Ehrenburg's health returned. He set to work trying to assist elements of the French government which still hoped to resist Germany. For this, the French government arrested Ehrenburg, although he was shortly released on the order of the Minister of the Interior. After the Germans occupied Paris, Ehrenburg left for Russia. When he arrived at the train station in Moscow there was no one from the Writers' Union on hand to greet him. When Ehrenburg turned 50 in January 1941, not a single Soviet newspaper took note of the fact. Anti-fascism was no longer in vogue. Because of the Soviet-Nazi alliance, Izvestia no longer printed Ehrenburg's articles, knowing his anti-Fascist sentiments. He did manage to print a series of articles in the newspaper Trud, which, despite numerous cuts and amendments, made his unpopular position clear. In early 1941 Ehrenburg completed the first part of his novel The Fall of Paris (Padeniye Parizha), covering France in the prewar years and the French decision not to intervene in Spain. There were no Germans in the story yet, and by changing the word "fascist" to "reactionary", the journal Znamya was able to print the work. The second part of the novel, however, was rejected. Undeterred, Ehrenburg sent a manuscript to Stalin, who then telephoned Ehreburg signalling his approval. The rest of the novel was published, and various journals started calling Ehrenburg with solicitations. In April 1942, the novel won the Stalin Prize. When Hitler staged the sneak attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, Ehrenburg was released as a ferocious literary weapon of war. During the war, he wrote over two thousand articles, mainly for the paper Krasnaya Zvezda. He gained credibility and popularity among the troops by frankly assessing German strength and admitting Soviet losses as well as expressing fierce hatred for the enemy. In one of his most famous articles he wrote: Now we understand the Germans are not human. Now the word "German" has become the most terrible curse. Let us not speak. Let us not be indignant. Let us kill. If you do not kill a German, a German will kill you. He will carry away your family, and torture them in his damned Germany. If you have killed one German, kill another.Soldiers loved his articles. An order was passed not to use copies of Ehrenburg's articles for rolling cigarettes. Molotov reported that Ehrenburg "was worth several divisions". On May Day 1944, Ehrenburg received the Lenin Prive for his wartime efforts. At least one Soviet officer, however, felt that Ehrenburg's articles went too far and incited Soviet troops to senseless violence, killing Germans trying to surrender. This officer, Lev Kopelev, was arrested and charged with "bourgeois propaganda" and "pity for the enemy". At one point, Ehrenburg got in a dispute with Krasnaya Zvezda over editing his articles. Stalin intervened, saying "There is no need to edit Ehrenburg. Let him write as he pleases." A true European snob, Ehrenburg was completely dismissive of the American war effort. According to Harrison Salibury, Ehrenburg thought Americans were "a naive, ignorant, uneducated colonial people who had no appreciation for European culture." American reporter Henry Shapiro wrote that Ehrenburg claimed the only contributions Americans ever made to civilization where Hemingway and Chesterfield cigarettes, which Ehrenburg was constantly trying to bum. A true Soviet man in his writing, Ehrenburg nonetheless refused to wear Soviet underwear and insisted that he wife keep mending his old French knickers instead. During the war, Ehrenburg and fellow writer Vasily Grossman undertook a project that was to be called The Black Book. Under their direction, over twenty writers worked to document the horrors suffered by Soviet Jewry at the hands of the Nazis. At first, the project was endorsed by the official Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Later, however, offical policy toward the Jews changed. The book was criticized for giving attention to traitors and collaborators among the Ukrainians and Lithuanians and publication became impossible. As the war approached its conclusion, Ehrenburg noted and spoke out against excesses of looting and rape committed by Soviet troops. Stalin was informed of these remarks, and on 14 April 1945 a severe rebuke of Ehrenburg appeared in Pravda. Ehrenburg was accused of "simplifying" the political situation and of calling for the extermination of the German people. Ehrenburg wrote to Stalin, justifying himself and pointing out the misinterpretations in the Pravda article, but he never received a reply. After the war, Ehrenburg took a triumphal tour of Europe. Then, in 1946 he visited the United States along with Konstantin Simonov and another writer named Mikhail Galaktionov. He of course met luminaries: Marc Chagall, Le Corbusier, John Steinbeck, Paul Robeson, Albert Einstein. He grudgingly came to admire America's technology, privately admitting to a friend that "Europe was two hundred years bechind the United States." But his impression of Americans as crass and boorish remained. Once back in Moscow, Ehrenburg quickly jumped into the cold war propaganda battle. He denounced the United States' Voice of America broadcasts in an article entitled "False Voice". In a small volume named In America he attacked the racial problems in the U.S. And in 1948 he wrote a play, Lion in the Square (Lev na Ploshchadi), a blistering, vicious attack on the behavior of Americans in post-war Europe. In 1949 he prepared a rather hysterical piece of anti-American propaganda named Nights of America. While consistent with Soviet attitudes at the time, it was, for some unknown reason, never published. In 1948, Ehrenburg produced the novel Storm (Burya) about World War II with action set both in the Soviet Union and in France. It described the enormous efforts of the Red Army to defeat Nazi Germany. While it contained descriptions of the massacres of Jews at Babi Yar, portrayed a shocking liaison between a Russian and a French actress (marriages with foreigners were illegal at the time), and made an oblique jibe at the Hitler-Stalin pact, it nonetheless won the Stalin Prize. Ehrenburg contributed to the cult of the personality, heaping praise on Stalin when and where appropriate. But occasionally he made small but noticeable gestures of a different nature. In 1947, despite Akhmatova's official status as an outcast, Ehrenburg went to visit her in Leningrad. When Andrei Zhdanov died in 1948, a tribute to him appeared in Literaturnaya Gazeta above the signatures of several prominent writers. Ehrenburg's name, however, was missing. In 1949 he hired a secretary whose father was in a labor camp. In 1949, Ehrenburg came close to extinction again as Stalin unleashed an anti-Jewish campaign. His work stopped appearing, and his name was removed from other articles. Perhaps somewhat prematurely, a Moscow party activist announced to a meeting that "cosmopolitan number one" [Ehrenburg] had been exposed and arrested. Ehrenburg wrote an appeal to Stalin. As a result, he received a reassuring phone call from Malenkov, and his works were again published. Ehrenburg was then dispatched a a Soviet delegate to the World Peace Congress in Paris. Also in 1949, he was elected to the Congress of Nationalities by a district in Riga, Latvia. He was to remain a deputy until his death. In 1950 Ehrenburg went on a propoganda junket to western Europe. For the first time, by his own admission, Ehrenburg was made to sweat by the hard-hitting questions of western journalists, particularly on questions relating to the Jewish situation. He tried to answer with ambiguities and generalities without having to resort to outright lies. But in this, he was not always successful. Ehrenburg's next novel was Ninth Wave (1951), a crude propaganda novel about the Peace Movement and the Cold War. Later it was renounced by Ehrenburg, who refused to have it included in his Collected Works. Anti-Jewish hysteria reached a new high in January 1953 with the announcement of the so-called Doctors' Plot. In mid-February, Ehrenburg and many other prominent Jews were asked to sign an open letter to Stalin acknowledging the passions aroused by the Doctors' Plot and asking Stalin to round up all the Jews and send them to Siberia for their own safety. Dozens of Jewish writers, artists and musicians, including Vasily Grossman and Margaritat Aliger--all terrified--signed the letter. Ehrenburg refused three times. He then wrote a letter to Stalin arguing not the morality of the idea, but worrying that shipping all the Jews off to Siberia would be a public relations disaster for the Soviet Union in the eyes of the West. Fortunately for everyone, Stalin suddenly died and the whole idea was forgotten. Shortly after Stalin's funeral, Ehrenburg quickly changed his tune. Instead of calling for orthodoxy, he wrote an article ("On the Role of the Writer") defending a artist's right to create according to his or her own inner voice, not according to some plan or directive. Then, in 1954, he published a novel that was to give its name to an entire era of Soviet history: The Thaw (Ottepel'). There is not much action in The Thaw, consisting mainly of interior monologues of a wide range of characters most of whom---willingly or unwillingly--are living inner personal lives at odds with their outer, public lives. The wife of an unimaginative but successful factory director struggles with her growing alienation from her husband. Others struggle to keep love out of their souls because it conflicts with their duties to the factory and to the Party. A talented artist who squandered his talent and became a hack for the sake of success struggles to maintain his cynical outlook so he won't have to face his own spiritual bankruptcy. But as the cold winter passes and the spring thaw comes, a change is beginning--loves and childlike exuberances with all their unexplainable contradictions are blossoming out into the open, with no regard to poltical correctness. Stalin and his passing are nowhere referred to in the work, but the time frame of the action is clear to the readers. Explosive for its time as well were passing references to the injustices of the terror and the absurd Doctors' Plot. Conservatives did not like The Thaw. Konstantin Simonov criticized it in an article in Literaturnaya Gazeta. Mikhail Sholokhov criticized Simonov for not being harsh enough in criticizing Ehrenburg. Ehrenburg worked to ressurect Babel's reputation, writing an introduction to a collection of Babel stories which, after some struggle, was published in 1957. He did the same for a collection of Tsvetaev and continued his vocal support for Pasternak as well as some of the better know of the repressed Jewish writers. He worked on a committee looking into the possibility of republishing the work of Boris Pilnyak. As a member of the editorial board of the journal Foreign Literature (Inostrannaya Literatura) he pushed for publication of the works of Hemingway and Faulkner. Ehrenburg was also instrumental in organizing the first-ever exhibit of Picasso's works in Moscow in 1956. Ten years later, in 1966, it was Ehrenburg who flew to France to award Picasso the Lenin Peace Prize. In 1957 Ehrenburg penned an influential essay, "The Lessons of Stendhal". Ehrenburg used Stendhal's remarks about tyranny as a not-too-subtle swipe at renewed calls for conformity and limits for writers. When Yevgeny Yevtushenko came under attack for his poem "Babi Yar" in 1961, Ehrenburg rode to his defense by writing a letter to the editor of Literaturnaya Gazeta. On his seventieth birthday in 1961, Ehrenburg was awarded his second Order of Lenin and a gala celebration in his honor was held at the Writers' Union. In his remarks at the party, Ehrenburg posited his belief that writers are not so much "engineers of the soul" as "teachers of life". In 1960, Ehrenburg began publishing the first chapters of his memoirs, People, Years, Life (Liudi, Gody, Zhizn). In the pages of this book he revived the names of many writers who had disappeared in the purges. He frankly admitted that he was aware of the injustices going on in the 1930s and that he participated in the grand "conspiracy of silence." Conservative critics were not pleased. Vsevolod Kochetov denouced: ...morose compilers of memoirs...who rake around in their confused memories in order to drag out mouldering literary corpses into the light of day and present them as something still capable of living.Attempts were made by those close to the government to discredit Ehrenburg, citing his confession of "silence" as an admission that he was a collaborator in the repressions. Everyone else, it was claimed, heaped praise on Stalin because they believed--mistakenly--that Stalin was telling the truth. If Ehrenburg--unlike everyone else--knew that injustices were being committed, his silence was immoral and his praise of Stalin makes him a downright dirty liar. That was the argument, but nobody believed it. Even Sholokhov, always hostile to Ehrenburg, dismissed it. With each new chapter of his memoirs, publication became more and more difficult. Ehrenburg was forced to make many changes and deletions. Explicit references to Bukharin were forbidden. At one point, further publication seemed impossible when Ehrenburg was subjected to fierce criticism from both Party ideologist Leonid Ilichev and boss Khrushchev. But as in so many things, Khrushchev later changed his mind, blaming everything on somebody else. People, Years, Life resumed publication, albeit with a preface from the publisher accusing Ehrenburg of "violations of historical truth." Ehrenburg lent support to younger writers. He signed a letter in support of Iosif Brodsky, counseled Andrei Voznesensky on how best to avoid complications, protested against the sentences given to Sinyavsky and Danil, and expressed positive views about Solzhenitsyn, although the future renegade lated lied about this, claiming that Ehrenburg "hated" his work. Ehrenburg continued to work on his memoirs until just weeks before his death. Following the writers's death, Andrei Tarkovsky tried to get these final pages published, but authorities demanded so many cuts and revisions, that the writer's family withdrew the manuscript rather than see an eviscerated version printed. It wasn't until 1990 that these pages were finally published Beset with prostate and bladder cancer, Ilya G. Ehrenburg died on 31 August 1967. Besides his undeniable talent as a writer, Ehrenburg had a remarkable ability to survive. According to the logic of the times through which he lived, Ehrenburg should have been executed at least three or four times. But, as Yevgeny Yevtushenko said, Ehrenburg "taught us all how to survive." A life full of changes and contradictions surely was his. But perhaps Ehrenburg himself described it best in his memoirs: If within a lifetime a man changes his skin an infinite number of times, almost as often as his suits, he still does not change his heart; he has but one. Sources: Rubenstein, Joshua. "Tangle Loyalties: The Life and Times oF Ilya Ehrenburg". Basic Books. 1996. Goldberg, Anatol. "Ilya Ehrenburg, Revolutionary, Novelist, Poet, War Correspondent, Propagandist: The Extraordinary Epic of a Russian Survivor." Viking Press. 1984. |

Return to: ENCYLOPEDIA OF SOVIET WRITERS

Return to: SovLit.net

editor@sovlit.net

(c) 2012 SovLit.net. All rights reserved.