Let's return to the beginning of 1925.

Moscow literary society was seething. The approximately ten literary associations, groups, and groupings existing at that time were issuing declarations and manifestos, which were constantly being "expanded" and "refined". Sharp discussions were on-going among the groups, reflecting the youthful fervor, the revolutionary zeal, and the passionate striving for new paths in literature.

At the time, as the comrades explained it to me, the Smithy1 was in an unfavorable position. Its most recent declaration, published in Pravda a year earlier, was outdated and in need of revision. In discussions, the Smithy caught it good, so to speak, for this "obsolete platform".

Another question was staring us in the face: to join RAPP2 or not? Yakubovsky, departing for a lengthy treatment at a tuberculosis sanitarium, spoke in favor of the Smithy entering RAPP. Sannikov and Filippchenko supported the same point of view. Bakhmetev and Lyashko were against the idea. Gladkov3 only laughed over the fact that RAPP members praised the Smithy as "the oldest proletarian group" and "the pride of the proletarian revolution" when the Smiths were moving toward unification, but when the Smiths insisted on autonomy, RAPP hurled all sorts of abuse at them.

I don't remember how, but Sannikov arranged for the Smithy to join RAPP, despite the opinion of the Smithy opposition. Fyodor Vasilevich [Gladkov] tried to placate the opposition.

He said, "Let's wait and see how the matter develops further. Maybe we'll be able to work with the RAPPers."

I shared Gladkov's opinion, and, what's more, it seemed to me that the very place for the Smithy was in the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP). I told myself that the difficulty in relations between the Smithy and RAPP was due only to the "inflexible character" of some of the Smithy "elders", their excessive punctiliousness and querulousness. When I became a member of the governing body, I decided to use all my strengths to facilitate the firming up of Smithy's position in RAPP.

Soon, however, I became convinced that the differences between the Smithy and RAPP were not due solely to the irritability of certain Smiths, but that there were other reasons, arising independent of the Smiths. This happened in the spring of 1925, on the eve of the publication of the resolution of the Central Committee of the RKP(b) on the policy of the Party in the sphere of artistic literature.

The draft of this resolution had already become known to those in literary circles. Such was the peculiar situation at that time--even Central Committee documents sometimes became well-known before their promulgation. There existed among professional journalists of the time those whose sole occupation was as oral "news disseminators" who dug up and divulged the most varied types of information, even those which sometimes should not have been divulged. From these "disseminators" it was learned beforehand that the Central Committee resolution would be directed against Communist arrogance among proletarian writers--it would be suggested that they earn the right to hegemony before adoring themselves with it. The free competition among literary groups was to be announced along with an uncompromising battle against ideological groveling. It was known that the Central Committee would condemn the privileged "hothouse" proletarian literature as well as the group monopoly in publishing matters. It demanded that critics banish the tone of command from critical articles and suggested that they demonstrate a solicitous attitude to different groups (referring here to the fellow travelers and peasant writers, but the Smithy saw itself as among those groups in need of a solicitous attitude).

The Smiths were impatiently awaiting the publication of the Central Committee's resolution. They liked everything they heard about it beforehand. They, of course, saw the accusation about Communist arrogance as referring to the leaders of RAPP and MAPP4. They supported the condemnation of the monopoly in book publishing and even began to expand their publishing plans--in this sphere the Smiths were not bad organizers.

Then, at the height of all this guessing and anticipation, the leadership of MAPP, without the prior agreement of the Smithy, suddenly called a city-wide conference of association members, to take place in the headquarters of the Moscow Proletkult. The Smithy was assigned 24 places at the conference and elected its delegates. F.V. Gladkov was elected as leader of our delegation, empowered to represent and advance the Smithy policy line at the conference.

At the appointed time the conference delegates gathered at the former Morozov mansion on Vozdvizhenka, which, at that time, housed the Moscow Proletkult and nowadays houses the Union of Society for Friendship with Foreign Nations. As if demonstrating its disdain for bourgeois culture, the Proletkult maintained this sumptuous palace in a trashy state--one could only guess as to its former shine and majesty. The dirty cloakroom was served by some slovenly attendant, and in the basin of the no-longer-functioning fountain, situated in the foyer, cigarette butts were piled up in abundance.

The plenary session of the conference was preceded by a session of the MAPP communist faction. It was suggested that the non-Party Smiths--Lyashko, Novikov-Priboi, Poletaev, Obradovich, Kazin and others--await the end of this meeting in the foyer, where, as I recall, there were not even enough chairs. N.N. Lyashko--who had been elected by no one but was acknowledged by everyone as the leader of the non-Party Smiths--was upset by this delay in the conference more than anyone else. "They could've told us to come an hour or two later," he reasonably suggested.

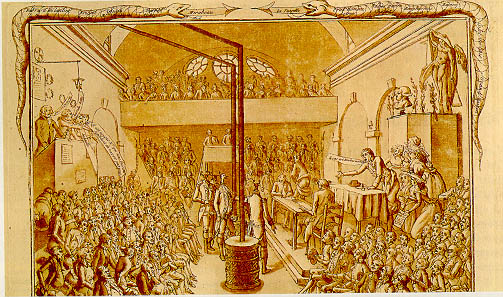

There were about ten Smithy Communists at the meeting-- Serafimovich, Gladkov, Bakhmetev, Pomorsky, Svirsky, I think Zhiga and a couple others. We entered the hall, which was set up like an amphitheater and for some reason reminded me of a Jacobins' club as portrayed in old engravings. We sat in a compact group somewhere on the left and--as it would seem later--too high up and away from the presidium. We looked around. RAPP was represented by all its bosses--even L.A. Averbakh, who was then on one of his periodic exiles from Moscow, had turned up for the meeting. (The leader of RAPP and the On-Guardists5 was periodically "transferred" to Party or newspaper work on the periphery under the supervision and care of two oblast committee secretaries--I.P. Rumyantsev and I. D. Kabakov--for terms determined by Stalin himself.) The press department of the Central Committee, which at that time managed literary affairs and was headed by I.M. Vareikis, had no one at the meeting. E. M. Solovei, head of the Moscow press subdepartment, represented the Moscow Party organization.

Engage in some nasty debate.

Join your local Jacobin Club

The chairman of the meeting--I don't remember who, maybe I. V. Vardin, or possibly the pink-cheeked F. F. Raskolnikov--suggested that we ratify the agenda of the conference on two questions: an organizational question, and the election of MAPP officers. As later developments in the meeting showed, the proposals on these questions had been agreed upon beforehand by the leaders of RAPP, the Octobrists, and other groups at the session; the Smithy Communists were merely being given the opportunity to vote along with an already established majority.

We talked among ourselves and decided not to give in. Gladkov took the floor and in a most calm tone (which was not very easy for him to manage) said something like:

"We all know, comrades, that the Central Committee decree on artistic literature will be published in just a few days. After that, we'll have to get together and plan measures for carrying out the Central Committee resolution. It's possible that some organizational questions will arise, the solution of which will help us better fulfill that resolution. And only then should we have elections; once we determine the attitude of our various comrades to the decree of the Central Committee, it will be easier for us to nominate for election those candidates who are ready to fight for the Central Committee policy on artistic literature. So is it worth it for us to have a conference now and adopt measures which, possibly, we'll have to review in light of the resolution of the Central Committee? And how can we elect people whose position on the most important Party decree is still not clear to us?! Permit me to make a motion on behalf of the Smithy Communists: adjourn the conference of MAPP until the publication of the Central Committee resolution, make no decisions today, and send everyone home..."

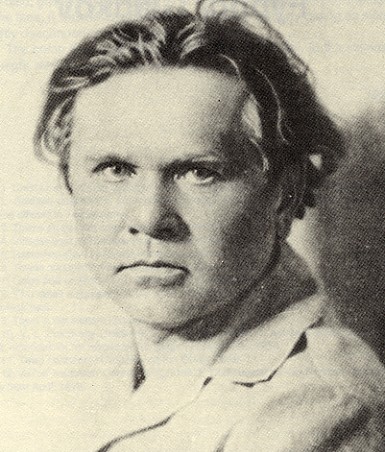

Fyodor Gladkov

E.M. Solovei spoke and supported Gladkov's motion.

Immediately, a whole cohort of RAPPers attacked her and Gladkov, declaring that MAPP is the leading organization of proletarian writers, which demands "urgent measures for the uninterrupted development of the literary process and for involving wide proletarian masses in this process", and that MAPP was not going to postpone or adjourn anything.

Someone snottily suggested that the Smithy was again intending to mark time, but that MAPP would shove it forward to attain new heights for proletarian literature.

The Smiths' motion was voted on and, of course, rejected by a decisive majority.

We returned to the agenda and the motions on the organizational question. They were crafty: it was suggested that the Moscow conference take the decision to dissolve all associations, groups, and groupings existing in MAPP--both Communist and non-Party.

Again F.V. Gladkov spoke:

"It's no secret," he pronounced, "that we all are acquainted with the basic elements of the draft of the long-awaited Party document. It proposes a creative competition among the different literary groups, and now, on the eve of the publication of this document, we want to liquidate all proletarian creative associations except RAPP, thereby establishing its complete hegemony. Just when the Party is getting ready to warn us that hegemony is still a long way off, and that it has to be earned. They want to warn us against a "hothouse attitude", but we aim to create a whole system of new 'laboratories' and 'hothouses'. The motions, as we have heard them here, contradict what comrade Frunze advised us at the Central Committee conference in March of this year. Why should we anticipate the Central Committee's resolution and take a decision contrary to it? Now, after hearing the motions on the question of organization, it has become even clearer that we don't need to be holding a conference today; but, unfortunately, you don't agree with us on this. We, the Communists of Smithy, propose one more motion: remove the "organizational question" from the conference agenda and, if you wish to continue the conference, move on now to discussion of elections."

Again the debate heated up, even more intensely. One of the speakers politely explained to the Smiths their "errors"--that they were, supposedly, exaggerating the significance of the proposed reorganizations, setting it up against the Central Committee resolution, the essence of which was really not yet known to anyone and which was, after all, still only a proposal. Others, including Lelevich, denounced "a new display of petite bourgeois deviation in the Smithy." Someone brought attention to the "insignificant number of Smiths" represented at the session of the Communist factions and suggested that Sannikov, Filippchenko, and Yakubovsky would probably agree with the proposed restructuring of MAPP. Then Pomorsky shouted out from his seat:

"Then let's put the question off until later and we'll find out the opinion of Yakubovsky and the others!"

The chairman of the meeting acted as if he hadn't heard this.

The session had been going on for two hours already. A break was declared.

"Confess! For how many pieces of silver did you sell out the Smithy?" Lyashko inquired of us when we emerged from the hall and went into the foyer. And he continued in his moralistic tone, "So much time wasted on idle talk! No, we have to end this and leave RAPP!"

When they found out that the session of the Communist faction was going to continue, the non-Party writers began to disperse and go home.

After the break, the debate cooled down. A little excitement was caused by the speech of V.M. Bakhmetev. In a quiet and ingratiating voice, without hurrying, he calmly said something like:

"I appeal to the leaders of RAPP. We know you pretty well, and you know us, too. We understood your suggestions on the organization question right away. You want to liquidate the Smithy at any cost. Things will be easier for you without it. It's a thorn in your side. It's a hindrance on the road to hegemony. To do this after the publication of the Central Committee decree would be impossible; and so you're in a hurry to deal with the Smithy before its publication. You're trying to trick not only us, but the Central Committee of the Party, too, presenting it with a fait accompli."

Howls of protest rang out. They wouldn't let Bakhmetev speak any more.

"Well, basically, I've said everything," he noted, raising his voice a little, and, stooping, he returned to his seat.

The picture was clear: the motion on the organization question would be put to a vote, the Smiths would be in the minority, and they would become involuntary participants in a crafty "restructuring".

What to do? Under no circumstances could we take part in the vote! Being secretary of the Communist faction of the Smithy required that I be resourceful. With a pencil I quickly wrote out a declaration about Smithy's resignation from RAPP because of basic difference of principle: we consider that the motions on the organization question proposed by the Communist faction of MAPP are contrary to the Party's policy on artistic literature and directed at disrupting the Party's aforementioned measures. F.V. Gladkov signed the declaration. The rest of Smithy's Communists signed it, too.

Before adding his own signature, A.S. Serafimovich asked:

A.Serafimovich

"Are we doing the right thing, leaving RAPP at such a moment?"

"They won't let us go, you'll see. And there won't be a vote on the organization question," I answered.

"And what will comrade Vareikis think about all this?" Serafimovich asked.

"He'll think the same thing we do," Gladkov answered for me, sitting next to Serafimovich and overhearing our whispers.

Once I got Serafimovich's signature, I practically ran to Presidium table, where the chairman was already standing to begin the vote on the organization question.

"Special declaration of the Smithy. We request permission to read it out immediately!" I said, holding a small scrap of paper out to him.

After the reading of our short declaration, a loud hue and cry arose from all corners.

"Oh, this is new! Now many times has the Smithy left? We won't let you back in this time."

"Do your non-Party members agree with this? You're acting behind their backs, you're bossing them around!" someone shouted out.

"No, we got their agreement during the break. They don't want to take part in any anti-Party business either."

"Oh-ho, so the Smithy Communists act on the orders of their non-Party members! The tail wags the dog!"

"They revealed differences in the Party faction to non-Party members! The Central Control Commission will hear of this!"

When the hall quieted down a bit, E.M. Solovei spoke "to restore order to the meeting" and said that it was impossible to permit the departure of the Smithy precisely now when the Party was demanding a sympathetic approach to all literary schools, except, of course, those hostile to us and that no one will particularly suffer if the organizational question, which has caused such sharp disagreements, were to be put off for a bit. And, after all, we should take pity on the non-Party members who have been waiting in the foyer. We should end the factional meeting as soon as possible and open the conference.

Someone else exhorted the Smithy, someone cursed us, but the damned organization question as if by itself disappeared from the agenda; and, not brining it to a vote, we moved on to discussion of candidates for the MAPP elections. The leaders of MAPP suggested a list with a significant number of Smithy representatives on it, and this list was accepted almost unanimously. We voted along with everyone else, as if underlining our satisfaction with the fact that the organization question had been put off and that we had received a sufficient number of places in the leadership. We decided not to make a public announcement about the withdrawal of our declaration about leaving RAPP, so as not to "taunt the geese" unnecessarily. Besides, everything was clear without it: if we were participating in the elections and joining the leadership board, it meant we were remaining in RAPP.

Some days later, Fyodor Vasilevich and I went to see I.M. Vareikis, who greeted us warmly. It turned out that Varekis in fact "thought the same thing we did". He agreed that our position was in line with the Party's policy on artistic literature and that our "maneuver" at the conference was tactically correct. We couldn't have asked for anything more.

* * * On the 1st of July 1925, the long-awaited Central Committee resolution "On the Party's Policy in the Sphere of Artistic Literature" was published on the front page of Pravda. The most different literary circles and groups greeted this document with satisfaction. It seemed that an end had come to RAPP's order-giving and to the abuse writers were subjected to in the journal On Guard, which had appeared sporadically since 1923 and which was edited by the literary troika "Volero" (Volin, Lelevich, Rodov). The last issue of this publication came out in June 1925, prior to the issuance of the Central Committee's resolution; and in a final blow aimed at the Smithy, it contained an article by a certain Al. Gerbstman. The poetry of the Smithy, previously damned as "Cosmism", this time was labeled "primitive hack-work", and Gerbstman picked apart Vasili Kazin as a supposed disciple of such poetry. F.V. Gladkov and the whole active group of the Smithy were greatly upset over this attack, but at the same time they comforted themselves: "For the last time, in the last issue! New times are coming, we will be happier looking forward!"

In the autumn of that year I had to fully immerse myself in preparations for the 3rd All-Union Conference of Workers Correspondents for Pravda. I was working on a speech for the conference and had to give up all other matters, including participation in the work of the Smithy. However, I would see Fyodor Vasilevich at editorial offices and at the Central Committee Department of the Press, and I would ask him how things were going with the Smithy. More than once Gladkov complained about the extremely complicated situation at RAPP, which had become VAPP6, and with the Smithy as well. The "new times" hadn't actually come to be. In place of On Guard, a new journal sprang up, borrowing a title from Lelevich (On Literary Guard--that was the title of a little book by Lelevich which came out back in 1924), but with the same, well-known Volero spirit. This journal carried on the same business as On Guard, just in a slightly softened form. At the Central Committee's Department of the Press, Vareikis was replaced by S. I. Gusev. A former military worker, he was a proponent of maximum clarity and order even on the literary front. In this respect, he was impressed with VAPP; through VAPP, it would be easier to simplify everything to a single denominator. And besides, VAPP guaranteed a supply of reserves: there was broad discussion of the decision of the 13th Party Congress to promote new worker and peasant writers from among the worker and agricultural correspondents. A VAPP with thousands of members already loomed on the horizon. The Department of Press suggested that literary organizations and groups conduct an exact count of their members, and VAPP showed an unbelievable growth in its writing cadres: from 717 persons on 1 October 1924 to 2,898 in the course of a single year; in the future, VAPP was planning on 5,000 - 7,000 members.

"This is pure eyewash on the part of Kirshon!" said Fyodor Vasilevich indignantly, for some reason considering V.M. Kirshon to be VAPP's "chief statistician".

The Smithy, along with the "Tvor" group which had joined it, had over the same period grown in membership from 49 to 100 and had no plans for further growth. These figures were too modest! At the Press Department Gladkov got an earful: "You Smiths are an exclusive group, pygmies, but VAPP, this proletarian Goliath, is relying on the entire worker and agricultural correspondent movement, on thousands of future writers! You had better latch onto VAPP if you don't want to be washed off the face of the earth by this mighty flood!"

The matter wasn't limited to discussions. The Department of the Press sent Gladkov a stern letter, which he passed on to I.I. Skvortsov-Stepanov, requesting the latter's involvement and protection. A.S. Serafimovich got it even worse. He was sent to work on the editorial staff of On Literary Guard, probably so that he might have an ennobling influence on the On Guardists.

"I'm on my way to see Gusev," Aleksandr Serafimovich informed me two months later. "I want to request that I be relieved of duties at the journal. There's nothing for me to do there. They listen to me, sometimes agree, but then do just whatever it is they want to anyway."

"Poor old Serafimovich," Gladkov once told me, talking about this. He's not very good at putting up resistance, and it's going to be hard for him to get himself out of this mess."

An extraordinarily frank and direct person, Fyodor Vasilevich himself was to no end upset over the "childish disease" of the VAPP circles of the time. For the rest of his life he expressed disgust with the demagoguery and idle talk, which, in those years, sometimes accompanied genuine revolutionary spirit and creative enthusiasm. Gladkov openly sympathized with several young writers who had joined the VAPP leadership, but he expressed regret that these gifted people wasted too much time and effort on the logomachy and the bad-tempered, not-always-justified "working over" of their own comrades, on composing causistic articles for the journal On Literary Guard. It bears noting that among the writers with whom he sympathized at that time was A.A. Fadeev, who also enjoyed great authority among the other S miths. Probably because of this, A.A. Fadeev spoke more than once at Smithy meetings on behalf of the VAPP leadership with recurrent exhortations.

* * * Years passed, fraught with great events, great achievements of socialist construction, great inspirational joys, and the bitter experiences of our people. The terrible storm of the Great Patriotic War, in which the spirit of our people sustained a great victory, passed.

It seemed that the bitter literary squabbles of the 20s had faded into the past and were long forgotten. However, from time to time, like it or not, these squabbles flared up anew in some article or speech of some clever lecturer who, attempting to "spice up" his lecture, would lash out at the Smithy, repeating the same characterizations and formulae which had disturbed the equilibrium of even the supremely calm A.S. Serafimovich.

At the beginning of the 1950s there appeared a book notable for its prejudicial interpretation of the literary phenomena of the 1920s (V. Ivanov, From the History of the Struggle for High Ideological Content in Soviet Literature). Fyodor Vasilievich and I noted the bilious lines about the Smithy. The author asserted that it was the Smith which was the "direct offshoot of the Proletkult, following in its footsteps both in theory and in practice", which "brought about a not insignificant harm to the development of Soviet culture." These malicious lines upset Fyodor Vasilevich. On that day, he was feeling poorly, fatigued and sluggish, but as he began to talk about Ivanov's book, he became more lively and talkative.

"Tell me, Fyodor Vasilevich," I asked him, "why is the Smithy so unlucky? Why is it precisely this group of Russian proletarian writers who get so painstakingly worked over? Oh, what arguments they had back then, and what labels they pinned on each other! Remember how even Gorky, when he returned home, was horrified at how such like-mined people--as he put it--could argue like enemies and try to hound each other with all their strength. And not just their contemporaries--they didn't spare the classics either. You remember how in 1919 On Literary Guard mercilessly worked over Chekhov on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death? But all this has been long-forgotten, has faded from memories. But when you talk about the Smithy, again and again they bring out the same arsenal of epithets and labels that were flung at it so long ago by Trotskyites, On Guardists, and whoever else cared to join in."

"You know perfectly well that I've always had a critical attitude toward the Smithy and that I've talked about its deficiencies more than anyone else,” answered Gladkov. "But nowadays they accuse it of anything that comes into their heads. 'Lenin gave a just and harsh criticism of Proletkult, so let's make the link between the Smithy and the Proletkult stronger!...' Besides, the six of seven Smiths who broke with the Proletkult at the beginning of 1920 comprised only the smallest part of the Smithy, and moreoever, two of them--Kirillov and Gerasimov--soon left the Smithy but did not return to the Proletkult. And Serafimovich, me, Bakhmetev, Yakubovsky, Novikov-Priboi, and almost all the rest were never in Proletkult and fought as hard as we could against the real Proletkultists, the Bagdanov remnants in RAPP; we spoke out more harshly than anyone else against the indiscriminate recruiting of workers and agricultural correspondents into VAPP, and against the "summoning of shock-workers to literature." These were all the Proletkult schemes of RAPP. I'll never forget how once when I was speaking to a group of workers correspondents, some On Guard demagogue shouted out: 'Comrades! Don't listen to him! Gladkov is your enemy! He doesn't think that you're writers!' MAPP, RAPP, and VAPP never left the Proletkult building on Vozdvizhenka, but we went there only at their invitation--and warily at that, always worrying that they might be drawing us into some trap... However, the 'literary historians' keep silent about the ideological and organizational ties of RAPP with the Proletkult and, as you see, they identify the Smithy as its 'direct descendant'".

"What's most incorrect and unjust," Fyodor Vasilevich continued, "is that these hasty 'researchers' view the Smithy as some sort of monolith, some sort of collective with a single face, never changing in membership, marching stubbornly in a single direction, all in accordance with the same 'declarations' for more than ten years. But in the history of the Smithy there were different periods, connected with the names and works of the most different sorts of people. There was the first period when the group was made up of poets, some of whom wrote poems characterized by a somewhat abstract and bombastic spirit called Cosmism. Then Yakubovsky joined the Smithy; Bakhmetev joined up, as did I and Novikov-Priboi; Serafimovich joined and walked hand-in-hand with us for several years--this was a different period, having nothing in common with Cosmism. Then came the time of VAPP trouble-makers like Berezovsky and Nikiforov, who brought the habits of passionate group struggle along with them from VAPP into the Smithy. At the beginning of the 1930s was a period of sharp struggles within the association itself--a struggle between the 'old' and 'new' Smiths. This was the final period, prior to the publication of the Central Committee's decree of 1932 dissolving VAPP and all literary groups."

I frankly confessed to Gladkov that I didn't know this period at all and couldn't even say what in essence the "old" and "new" Smithys were arguing about.

"You see what happens! Even you don't know!" Gladkov exclaimed. "So how can we talk about the Smithy as a homogenous, single-faced, Proletkult-Cosmic movement? Is it fair to assign to the Smithy all the crazy ideas and turbulence into which the individual writers of the declarations sometimes fell? Is it fair, finally, to be so particularly rancorous in regards to the Smithy? The group could be forgiven much if only for the fact that none of the Smiths ever even dreamed of saying or writing filth such as was published about Chekhov--and that wasn't even in the beginning of the 1920s, but at the end of the decade...."

At the end of this conversation, we lamented over the fact that we had often intended but never actually managed to produce an article or open letter about the Smithy which would help conscientious literary researchers understand its past, the--at least--four separate periods of its activity, and to distinguish its genuine transgressions from imaginary ones, to distinguish the truth from slander.

Footnotes:

1Smithy. Proletarian literary group formed in 1919 as a break-away from the Proletkult, which, the Smithy founders believed, was holding back their creative development. (For more information see "Proletkult & the Smithy, Thin Journal #1, Jan 2006, and "Smithy: A Smithy Manifesto", Thin Journal #3, Sept 2006. Also available at http://www.sovlit.com/bios/smithy.html and http://www.sovlit.com/bios/proletkult.html

2RAPP. The Russian Association of Proletarian Writers. The group demanded proletarian hegemony over all of Soviet literature, condemned the "fellow-travelers", and engaged in bitter clashes with the Smithy, LEF, Pereval, and other literary groupings.

3Gladkov. Fyodor Vasilevich Gladkov. Author of the seminal socialist-realist novel Cement. For further information see: http://www.sovlit.com/bios/gladkov.html

4MAPP. Moscow Association of Proletarian Writers. A branch of RAPP.

5On-Guardist. Members of the "October" or "On Guard" faction, an ultra-orthodox subgroup of RAPP. They published the journals "On Guard" and "On Literary Guard".

6VAPP. All-Union Association of Proletarian Writers.

Original text from: F. Gladkov - Vospominaniya sovremennikov, Sovetskii pisatel', Moskva, 1965.

Translated by: Eric Konkol

Return to: SovLit.net

Address all correspondence to: editor@sovlit.net

© 2012 SovLit.net All rights reserved.