"Marina's Illness"

by

Vikenty Veresaev

(1930)

a story of love, sex,

and abortion in early Stalinist times.

presented by

oth of them, Marina and Temka, were overburdened with work. There were studies and their social load, and they had to work for their miserly stipends. From early morning till late at night their hours were completely occupied. From the auditorium to the laboratory, from the session of the faculty commission to the bureau meeting of their Komsomol cell. Days followed one after another as if in a dream. Sometimes you completely lost the feeling that you were a separate individual, a living human being, that you might have your own particular interests, different from those of others.

And suddenly there rose up in front of both of them something of their own--very serious and important, concerning only them and of no interest to anyone except themselves.

On Saturday, as always, Temka left the hostel to spend the night with Marina. Her eyes were particularly bright. Suddenly, in the middle of conversation, she grew thoughtful. When he embraced her waist and wanted to kiss her neck, Marina stayed his hand and said, gazing steadily at him with her sunken eyes that had dark lines under them:

"Temka! This is important. I'm pregnant."

He quickly dropped his hand and stared at her.

"Really?!"

"Yes. I went to the doctor. He said so."

Temka--tall, strongly built, and with a large head--slowly paced the narrow room. Marina gloomily followed his movements. From deep inside him arose a burning, completely unreasonable joy, a feeling of exhalation, some sort of pride. He was so shaken that he couldn't utter a word. This was so unexpected for him, this foolish joy and celebration. Temka burst out laughing in amazement, sat on the bed next to Marina, took her hand into his wide palms and said with happy distress:

"Well, well!"

Marina was glad that he reacted so well to the news. Deep in her soul, she, too, was happy about what had happened. But this didn't make her feel any better. The situation was very complicated. She asked:

"What are we going to do? Just imagine, concretely, what's going to come of all this?"

"Yes, yes...."

He began to speak distractedly. Temka was still taken with his unexpected, inexplicable joy. He placed his hand on her still girlish, tight belly and gave a squeeze.

"Amazing! Just think, something is growing inside you; yours, and at the same time mine. Ha-ha-ha!"

He laughed with his full throat. Marina got angry.

"We have to think seriously and he's roaring like a fool. Shut up, please!"

"But doesn't this make you happy?"

"To hell with happy! I just feel sick all the time. Oh, how sick I feel. And my breasts hurt, and you're so disgusting. Please, don't touch me!"

Marina abruptly shoved his hand away from her body.

Today they could agree about nothing. Their moods were too different. But it was a menacing question, and they had to come to a decision quickly. Marina, overcoming her strange disgust of Temka, agreed that he should return in three days so that they could discuss everything.

But in reality, what was there to discuss? The matter was absolutely clear. Temka came to understand this intellectually in the morning when he gave it some sober thought:

Nonsense. There's only one way out.

And in the depths of his soul there was an anxiety over what they intended to do and a puzzlement--would Marina really stoop to this action?

Three days later they spoke. Yes, they had to make a decision. There was no other way out. Marina wrung her hands with anguish and said:

"I'm so sick all the time! I can't think of anything, no matter what! And there's a test in organic chemistry two days from now!"

Temka looked at her furtively and felt a secret pain over that fact that she was taking this step, and taking it so easily.

First, she had to take two exams; Marina had been preparing for them for a long time and it would be impossible to put them off. She had horrible fits of vomiting and she could think of food only with horror. Her head was just not working. And then there was Temka. Although it was incomprehensible even to her, she felt a growing hatred toward him. When he tried to embrace her, she winced. She told him:

"Please, visit me less often. I find you really unpleasant."

The female doctor examined Marina and questioned her about her living situation.

"Yes, yes. It's a common story. As a doctor, of course, I am required to dissuade you by any means possible, but if I were in your place, I would do the same."

And she gave her an order for the clinic.

Three days later Temka brought Marina back to her room. Marina was all pale, her face was sunken, her eyes moved slowly and stared off. But they gazed at Temka with a welcome affection. (He had already given up hope of this ever happening again.) Marina lay down and tenderly stroked his wide hand, looking like the hand of a former hammerer.

He asked:

"Was it very painful?"

"Physically, not so much. Having a tooth pulled hurts a lot more. But it's so horrible...."

She was trembling all over. She squeezed his hand tightly and pressed it to her cheek. And she was silent for a long time.

In the evening she said:

"It's frightening in its cynicism. Like prostitution. It seems strange to me now that a woman could bring herself to do this. I can't imagine it, just as I can't imagine selling yourself for money. It could warp your whole soul...everything that they did to me there. The mark of depravity will forever lie on the lips, and suffering and cynicism will freeze in the eyes. The legal butchering of future people. I can't think of it any more."

The evening was warm and tender. Marina soothed her soul in the love and guilty embraces with which Temka surrounded her. But her thoughts kept coming back to what had happened. When they put out the light (Temka was spending the night with her and had arranged himself on the floor) she said:

"Remember, in autumn there was article in the Red Student? I keep thinking about it. How did it go? 'Our days are filled not with the scent of lilies and wild flowers, but with the scent of iodine. Who will be talking of our commonplace student love while crucified on the Golgotha of the gynecological throne?"

That night, through his sleep, Temka heard Marina quietly crying.

Life returned to its normal course. Both of them--Marina and Temka--again were swirling in the full swing of work where their days disappeared; the auditorium was again followed by the laboratory, the bureau of their Party cell, the faculty commission. In their mutual relations, Marina and Temka became more careful, more mature. The unexpected complication which had occurred was not repeated.

A year and a half passed. They both were nearing graduation.

Marina passed her final exams and was getting ready for her dissertation. Temka was also facing a dissertation as well as three months of practical industrial work.

And then this happened.

On a Saturday, Temka came over to Marina's and they went out to a movie.

A worker-revolutionary. Morning. He's sleeping. His four-year-old son runs in to wake him up. The father romps around with the little boy, plays with him. Then the boy goes into another room and wakes up a student who's living with them--also a revolutionary, who, as it turns out, is a traitor.

And again the child's laughing little face, that sweet nature which animals and children project on the screen.

In the darkness, Marina pressed herself to Temka's elbow and asked excitedly:

"He's such a wonderful kid, isn't he? How lovely!"

Temka listened in surprise. What's she so excited about? He's a kid like any other. She was completely indifferent to the exploits of the invariably firm revolutionary-workers and to the treachery of the student. She just kept waiting to see if the little boy would show up again.

When they left the theater, Marina kept gushing about the boy, so Temka grinned and said:

"Why do you like him so much? He's an ordinary little snot-nosed kid. Nothing special."

Then Marina argued with Temka over some trifle and, on the porch of her building, she said to him, "Good-bye", and he, sad and bewildered, dragged himself back to the hostel for the night.

After this, something strange happened to Marina. She was sitting alone in her room, studying for a geology test or reading The Agitator's Companion. She heard the low crying of an infant on the other side of the wall. Her neighbor Alevtina Petrovna had recently given birth, and her child was very restless; it was crying all the time. Marina stopped reading and, falling into thought, she listened for a long time. She pressed her breast to her hand and against the edge of the table. She felt her breast and thought: she didn't need a man's hand caressing her breast or the kisses of a man's lips. There was only one thing she wanted. She passionately wanted to hold a tiny body in her arms and to have tiny lips sucking on her. Everything which before had attracted her and had been so intensely sweet for her now seemed dirty and burdensome.

Marina lit the primus stove in the kitchen and put on the kettle. Citizen Sevriugin-- Soviet trade worker and Alevtina Petrovna's husband--entered the kitchen. In an apologetic tone he said:

"Our little one bawls a lot. He's a little unmanageable. And you have to study. Does he bother you a lot?"

Marina looked at him in silence for a moment, then quickly answered:

"He bothers me. I'm very jealous."

And she rapidly left the kitchen.

Once after lunch a flustered Alevtina Petrovna knocked on Marina's room and said:

"I'm so ashamed to have to ask you. I just remembered my ration card for oil expires today. I have to go to the shop; there's a long line there. You can hear everything through the wall. If my baby starts to cry, could you look in on him? Forgive me, please. Kids are so much work, a real pain."

The child was already crying on the other side of the wall.

Marina put down her geology textbook and quickly stood up.

"I'll go right now. It'll be my pleasure. And you don't have to hurry."

They went into the adjacent room. Alevtina Petrovna said:

"I'm so sorry. I'm being so bold. I have some water warming up in the kitchen. I wanted to give him a bath today. Could you look after the water, too?"

"Yes, fine, fine, I'll take care of everything. Go."

"Thank you so much. If he gets wet, there's a dry diaper hanging over here."

She left, smiling gratefully.

The child was crying on the bed. Marina picked him up and started to carry him around the room. She murmured comfortingly:

"Oh, don't cry!"

She pressed her lips to the satiny skin of the baby's pudgy forehead.

The baby stopped crying, but he didn't go to sleep. Marina wanted to lay him on the bed and get back to her textbook. But she kept looking at the child and couldn't tear herself away from him, touching her lips to the fine and few golden hairs on his temple. She snapped her fingers in front of him, trying to make him smile. It's disgraceful! She's got a tough geology course to study for and she's decided to play dolls?

She laid the child on the bed, sat down at the table, and opened her textbook. But the boy began to cry again. Marina felt the diaper: it was wet. She was secretly happy that she had to deal with him again. She took off the diaper, placed him down on a clean one with excessive care, and she wanted to wrap him up. But she got lost in admiration. In the tiny, thin little shirt, reaching only to the middle of his tummy, he waved his pudgy little legs, muttered in concentration and stuck his tightly clenched fist into his mouth.

Foolish tears of melancholy and an abstract resentment began to well up in her chest. Marina bit her lip. Her shoulders drew back. She felt sharply--almost palpably--how dear to her were these full arms with dimples on the elbows, the wrists crossed with deep folds, and indeed all of this delightful little body. It was as if she saw things with new eyes. There was something before her that was extraordinary and incomparably sweet.

For the entire hour, Marina did not touch her textbook. Alevtina Petrovna returned and again began to apologize and gush with gratitude. Marina asked:

"Are you going to bathe the boy now?"

"Yes."

"May I watch?"

"Certainly! Of course!"

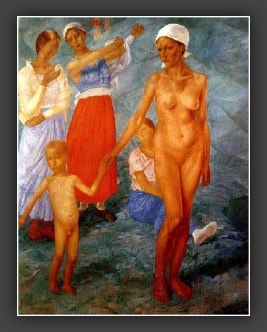

Warm steam rose from the zinc washtub. Alevtina Petrovna spread out some soap, a sponge, and a box with powder on the table. They undressed the child and started to check the water temperature with a thermometer. The naked boy lay crosswise on the bed, wiggled his legs, and burst into a mumbling wail. His mother, with her sleeves rolled up, picked him up and held him above the washtub with his entire body resting on her soft, white arm; then she lowered him into the water.

The child immediately began to cry, opening his eyes wide and letting out a surprised "Ohh!"

The light from the electric lamp under a green shade fell from above. The boy slowly moved his legs in the water that was sparkling with green reflections as he stared intently at the ceiling. His mother wanted to start lathering up his head, but she noticed his look and stopped. And she smiled.

"See, how he's looking!"

With wide, peering eyes, the boy gazed upward as if there was something in front of him which he alone saw but was hidden from everyone else. He became quiet. He kept looking seriously and carefully, without blinking. It was as if he were remembering something, remembering something far away and ancient, from a time when the world was as young as he is now. And it was as if he felt the limitless ocean of life--an ocean in which he was a small but integral drop--splash above and around him.

He again let out his surprised "Ohh!" and continued to gaze upward.

Marina paced the room in agitation.

That evening, Temka came to call. As they spoke, Marina fell so deep into thought that Temka finally asked in surprise, "What is going on with you?"

"Nothing."

She pressed herself warmly to him. The night was long. Their conversations were long. Passionate and strange.

"No! I don't want that!"

"But, Marina, what is wrong with you? Do you really want things to be the way they were a year and a half ago? What do we need children for now? Just wait. Let's graduate. It's not that much longer."

Marina answered defiantly:

"We don't need children?! Speak for yourself. You don't need them? Think. The most important thing is, do you want this or not? Temka! Understand!"

She sat on the bed in the darkness and wrung her bare hands. "I want a tow-haired, whining little boy sticking out his arms and crying, 'Mama!' I want it so much it's like a disease and I don't want to think about anything else. And you're just disgusting, repulsive; everything's disgusting...unless I have a child!"

Temka jumped up and quickly stated to get dressed. He turned on the lamp. Marina watched him from under the blanket with hostility. It was four o'clock in the morning. He left angrily.

In the end, Temka had to give in. And Marina got what she wanted.

Again things were very difficult for her. Again nausea tormented her, and her head constantly ached. But a sweet expectation lived in her soul, and Marina carried all her burdens with triumph. When confined to bed, she boldly took up her textbooks again. With enthusiasm she led a group discussion on current politics at the spinning mill.

The months passed. One day, Marina returned home from the factory club along with the girls from her circle. They were passionately discussing the revolutionary movement in India, Gandhi, the assault on the salt warehouses and the "red shirts". Komsomol-worker Galya Andreeva looked at Marina's protruding stomach and said:

"Ah, Marinka, Marinka! You're so wrapped up in current politics. You see everything the world over, what's going on where and what it all means. But what's going to happen in autumn?" She questioningly laid her hand on Marina's belly. "You'll abandon us. It's always that way. She has a baby and a girl gives up all her work."

Marina burst out laughing.

"You're a fool, Galka! Before resorting to such philistinism I'd rather hurl myself off a bridge into the Yaooza River. It is possible to have a child and continue with social work."

Another Komsomol-worker, who had a husband, sadly countered:

"That's what we all say. You still don't know how much work a child is."

"Just wait, you'll see," Marina said with self-assurance.

Marina was often seized with a feeling of weariness and helplessness. Sometimes on the street, and particularly when standing in line for bread or milk, her head would start spinning. And in general, living on her own became more difficult.

Temka left the hostel and moved in with her. He helped as best he could and with what time he had. He was tender and attentive to Marina. But it was awkward for him now walking along the street with her when people they met, particularly women, threw quick and thoughtful glances on Marina's protruding belly. And how her way of walking changed!

Before, she walked quickly as if on springs, but now she waddled from leg to leg like a goose. She spread her legs wide when sitting. Temka now noticed how, in general, she was not pretty. Marina had never really been beautiful: snub-nosed with numerous freckles and unruly hair, cut a la foxtrot. But she had something strong, healthy, and ardent in the Komsomol style. Now her freckles had fused into a single dark-brown spot, covering the bridge of her nose and her cheeks. But her lips were white. A constant exhaustion gazed from her eyes.

However, despite all this, Temka was strongly drawn to her. For him, she was, as before, desirable. But she found his embraces completely intolerable; she convulsively shoved away his arms, with disgust written on her face. Temka knew very well that all of this was normal and completely keeping with the laws of nature, but still in his soul he felt offended. He was even more offended by the fact that Marina was coarse and prone to outbursts; but Temka always felt that for her he was the closest and most dear person.

He clearly saw that Marina very rarely thought about him; all of her thoughts, like a compass needle, were drawn to that person slowly growing and ripening inside her body. This was somehow particularly insulting.

Sometimes, through the fog of constant activity and thoughts not concerning him personally, an idea broke through into Temka's mind like a bright spark: "parents". And he quite distinctly imagined how this sand would be spilled into the moving parts of the rapidly working machine of their life. He shook his head and muttered distressfully:

"Well, well!"

One evening they were sitting together, working through the points of the upcoming Party conference. Temka was reading; Marina was listening and sewing shirts for her future child. Proudly spread out on the table was some cotton material which they were fortunate to purchase that day; Marina had already cut it up for diapers.

Three short rings. For them. Temka went to unlock the door. His loud, nervous laughter resounded in the corridor. He said to someone:

"Wait here! One minute!"

He quickly entered the room and whispered excitedly:

"Quick! Clear all this away!"

Marina asked in surprise and threateningly:

"Clear what away?"

Temka whispered guiltily:

"It's Vaska Maiorov, the regional secretary."

"So?"

Temka threw up the lid of a basket and quickly started to toss the cut-up diapers from the table into the basket. Marina sat immobile and watched him. He again dashed to the table, grabbed her sewing, pricked himself on a needle, swore, crumpled up the shirts and shoved them into the basket as well. He slammed the lit shut. Sucking his pricked finger, he went to the door.

Maiorov entered--haved with thin, mocking lips. They talked about the upcoming Party congress. Marina took no part in the conversation, sitting silently on her chair and tapping a pencil on a book that was on the table--first on one corner, then on another.

After half an hour, Maiorov departed. Marina continued to sit silently and started at Temka. He tried to avoid her gaze.

Suddenly, Marina said gravely:

"What a disgusting mug you've got!"

"What? What are your talking about?"

Marina was silent and continued to stare gravely at Temka.

Then she pronounced slowly and authoritatively:

"Here's what, my dear comrade! Get out of here!"

"Marinka! What's with you? What's happened to you?"

"You don't understand? Too bad for you. Shove off! I don't want to live with you anymore."

1930

Translated by: Eric Konkol

See also: Biography of Vikenty Veresaev

Return to: SovLit.net

Address all correspondence to: editor@sovlit.net

© 2012 SovLit.net All rights reserved.