Presents a summary of:

CHAPAEV

by Dmitri Furmanov

(1923)

Ivanovo-Voznesensk Home of the first Workers and Peasants Soviet Tell them  sent you! |

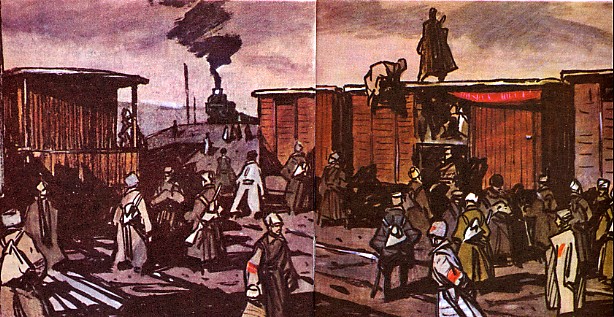

Late one cold night in January 1919, a detachment of 1,000 Red Army soldiers, recruited from among weavers in Ivanovo-Voznesensk, are getting ready to board a train to join the fight against Kolchak. Among the recruits are 26 women. Accompanying the troops as political officer will be Fyodor Klichkov, a worker from Moscow who discovered during the Revolution that he was good at organizing.

The platform is crowded with an endless sea of family and well-wishers from the factory. Before departure, Klichkov makes a speech, bidding the townsfolk farewell. He urges the citizens to take care of the families and children that the departing soldiers are leaving behind. And he says, "Always remember that victory doesn't depend just on our bayonets; it depends on your labor, too." Some of them may die, Klichkov notes, but there's no use crying about that because the Revolution doesn't count individual victims.

One of the departing women soldiers, the 22-year-old Yelena Kunitsina, also give a speech, telling the workers to keep things together on the home front; otherwise all their struggles over the last years will have been in vain.

A tearful and grizzled old fellow climbs up onto the platform and, on behalf of all the fathers, gives his blessing to the departing troops, even though he knows that some may not come back. He tells them that the main thing is that they shouldn't fall down on the job, and he pledges that those staying behind will do what they can to help the war effort.

At the stroke of midnight, amid tears and joyful shouts, the train carrying the soldiers pulls out of the station.

|

|

The closer they got to Samara, the cheaper bread became, which was a surprise to the worker-soldiers, who were used to treating bread like a valued treasure. They bewailed the sad state of ties between the cities and the grain-producing regions.

Read: Frunze's Life Stalin's Speech at Frunze's Funeral Tell them  sent you! |

Soon, two three-horse sleighs were galloping out of Samara with Klichkov and the three others: A 23-year-old turner and Petrograd native named Andreyev, the tall Lopar, and Terenty Bochkin, a 28-year-old red-head, good-natured and friendly.

THE STEPPE

As they ride along in their sleigh, Bochkin and Lopar try to draw their peasant driver into conversation and elicit information about the region and the strength of its Soviet. The driver, however, is sly and evasive and won't give a straight answer. The only thing he does say is that Gorshkov, the head of the Soviet, is unfair in giving out orders.

In the other sleigh, the driver is Grisha, a 22-year-old farm laborer who looked like he was 35 and who had lost a leg while fighting with Chapaev. Klichkov keeps pumping Grisha for stories about Chapaev, whom Grisha describes as a true hero. He sadly remembers the time when Chapaev and his troops arrived too late at the Ivanshchenko Factory to save the two thousand workers butchered by Cossacks.

Grisha admits that at times Chapaev and his men had to use force and intimidation, even beatings, to requisition food and supplies from the peasants. Once Chapaev smashed Grisha in the ribs with a rifle butt as punishment for wasting ammunition by shooting at birds.

The travelers stop off in the village of Ivanteyevka for about a hour and a half, then they set off again. This time, as they cross the steppe, a fierce snow storm lashes at their faces, but still they make it to the village of Pugachev where they find places on a train load of political workers. The train is frequently delayed by breakdowns and snowdrifts on the tracks, so it takes them two more days to get to Uralsk.

URLASK

URLASKWhen Klichkov and the others arrive in Urlask, they learn that Frunze has already left to be closer to the front to direct a newly undertaken offensive. The town was like an armed camp filled with unruly, undisciplined peasant soldiers. The disorganization was partly due to the fact that there were very few Communists among them, and half of those were fakes. Shady agitators told the peasant-soldiers that Communists were nothing but brutes and rapists. Confused, many peasant-soldiers asked what was the difference between Bolsheviks and Communists. When the Ivanovo-Voznesensk regiment arrived two days later, these "free" peasant soldiers would fire at them from around corners, fearing that they had arrived to take away their freedom. Soon however, trust and friendly relations developed between the two groups.

There were two main Communists in Urlask: Fugas (i.e, "Land mine"), a battle-tested miner of fine character; and Pulemyotkin, a wretched little intellectual, a political humbug and poseur whose personal qualities arouse thorough dislike.

Later that day, Klichkov and the others receive word that Frunze has returned and they rush to meet with him. At first, the newcomers are surprised to see Frunze surrounded by military experts--former colonels and generals--all of whom treat Frunze with much respect and deference. But with his fellow townsmen Frunze is the same old, direct, honest, and informal comrade they've always known. He explains the military situation to them and talks over old times. Tomorrow, Frunze is leaving for Samara. He says he'll send them appointments to work in the Army soon, but for the time being they should work with the local Party Committee.

After the meeting, the newcomers look in dismay at the state of anarchy among the soldiers. Andreyev notes, however, "We've fixed worse situations than this. We'll put things right."

The 23rd of Februrary was approaching, the anniversay of the founding of the Red Army. Lopar discovered that no one was in charge of arranging a celebration. At his insistence, a meeting was called, but was poorly attended. Lopar, undeterred, declared the meeting competent and got underway. He was declared chairman of the celebration organzing committee, and Andreyev the secretary. They decided where meetings would be held and who would speak. They organized workers to construct speaker platforms, pass out leaflets and placards. The arranged for better food and theater entertainment for the children.

On the day of the celebration, everything was ready. Workers and soldiers jammed into the central square. They gave a warm recpetion to Fugas. Pulemyotkin then jumped up and droned on for 30 minutes, chewing over old platitudes that everyone was already tired of. He would have kept going if Lopar had not stopped him. In the evening, there were shows, films, and more speeches. This time, fortunately, Pulemyotkin was held back and didn't get a chance to speak. Lopar game an impassioned talk about the fallen comrades. After a momentarily silence, the soldiers all began firing their guns into the air as if in a celebratory salute, but really just a rowdy, dangerous, chaotic display.

Klichkov and Bochkin spend the holdiay at the front, where the soldiers are happy to see them, glad that they have been remembered. They listen eagerly to Klichkov and Bochkin's speeches and ask them to come again.

A few day later they receive their orders. Lopar and Bochkin are to go to Brigade Headquarters. Andreyev is to stay in Uralsk as commissar. And Klichkov is to move on to Aleksandrov-Gai to organize political work in an army group being set up under the command of...Chapaev!

ALEKSANDROV-GAI

ALEKSANDROV-GAIKlichkov makes it to Aleksandrov-Gai, where the political work is being headed by the 22-year-old Petrograd worker Nikolai Nikolaievich Yozhikov. Yozhikov has the respect of the soldiers and the village inhabitants because of his plain, sensible speech. He is true to his word, never makes empty promises, and is always with the soliders on the march and in battle. At their first meeting Klichkov immediately sees that Yozhikov is a dedicated and competent worker and that he has everything well organized. For some reason, however, Yozhikov seems somewhat aloof. Klichkov thinks Yozhikov is irked that Klichkov has has come to supplant him as superior. This is despite the fact that Klichkov has come not to command, but to work and that the question of subordination did not bother him in the least.

Klichkov sets to work, first of all reading the minutes and reports; then calling small meetings of Party cells, cultural commissions, economic commissions, military commitees, etc.; then inspecting all the units. He learned that pamphlets were being accurately and zealously distributed to the regiments and that libraries were being organized. But the schools for fighting illiteracy had practically stopped working because of the military activity. Amateur-talent performances were often put on and well-attended.

An offensive was scheduled to begin soon. The army group in Aleksandrov-Gai was to move on the village of Slomikhinskaya and dislodge the White Cossacks there. But with two days until the beginning of the offensive, Chapaev had still not arrived to take command. Klichkov attends the final strategy conference at Staff Headquarters. The success of the attack would rely not so much on surprise as on good organization and Red superiority in weapons, particularly machine guns.

Klichkov, who was still weak in military matters, did not speak at the meeting. But he scrutinzed the face of everyone there, thinking, "Can he be a traitor?"

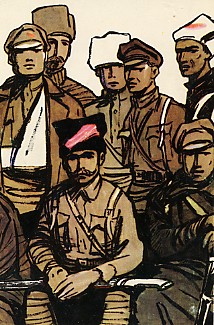

CHAPAEV

CHAPAEVAround 5 or 6 in the morning, Klichkov is awakened by a knock at his door. It is Chapaev and his retinue. Chapaev's men barge right in and make themselves at home. They are rowdy and undisciplined among themselves. But when Chapaev speaks, it is a different matter--they become attentive and obey his orders immediately.

Along with Klichkov, the whole group head out for staff headquarters. Klichkov feels that Chapaev is paying too little attention to him, treating him like one of his "suite".

|

|

Klichkov has a plan to intellectually capture Chapaev. At first, he would avoid military discussions so as not to reveal his complete ignornance in this area. Instead, he would hold discussions on politics, science, education, and general development, where Chapaev would listen more than talk. Klichkov would take the opportunity to draw out Chapaev, learn his opionions and personal details. Finally, Klichkov would have to prove himself as a brave soldier; otherwise Chapaev would view him with contempt as a lily-livered intellectual.

|

|

After the meeting ends, Chapaev goes outside, where a crowd of Red Army soldiers greet him with cheers. He tells the soldiers that he has no time for speeches and that he'll see them tomorrow on the front lines.

Chapaev, his retinue, and Klichkov set off across the snowy steppes. Klichkov thinks, "Tomorrow will mark the beginning of a new life for me." Chapaev rides for a bit with Klichkov and angrily denouces all Cossacks. Klichkov tries to point out that not all Cossaks are bad, and that there are even some serving in Chapaev's own command. Chapaev grudgingly admits that there might be one or two good ones, but insists that it is wishful thinking to expect any good from the Cossacks.

Chapaev also rails against the Red Army Academy, filled with old generals. Chapaev attended one of these academies for a few months, but abandoned it because it had nothing useful to teach him.

THE BATTLE OF SLOMIKHINSKAYA

Chapaev and his group stop in the tiny village of Kazachya Talovka, which has been burned to the ground. He crowds into one of the few remaining huts with commanders and soldiers and reviews with them the battle plan for the next day. After the business is finished, Chapaev leads the men in some singing. (Chapaev always sang for 10 minutes a day, otherwise he would get depressed.) Klichkov felt out of place, even lonely, in this closely-knit family of soldier comrades.

Before dawn, the battle begins. Shells explode, and immediately carts start streaming back from the front lines, carrying wounded. Contact is lost with one of the regiments. It seems that its men became suspicious of thier commander, a former tsarist officer, so they refused to obey his orders and did not advance. A snow-storm flairs up, halting the advance; but soon it dissipates and movement continues.

The Cossacks abandon the village of Ovchinnikov after only a token show of resistance. The Red Army troops move across a wide, flat plain toward Slomikhinskaya. They could be easily shelled from the village, but for some reason the Cossacks were silent. Klichkov rides on his horse in front of the skirmish line; an act of bravado, to be sure on the part of this commissar never before tested in battle, but still it encouraged the troops and raised their opinion of him.

When they got within 600 meters of the villiage, the Cossaks opened fire with artillery and machine guns. Klichkov was immediately thrown into confusion. He hid behind his horse for a while, then jumped in the saddle and galloped off. Now he was no longer in front of the skirmish line, but behind it. Not knowing where to go, he gallops to the left flank. He meets up with Popov, one of Chapaev's aides, who is galloping in the opposite direction. They exchange a few questions, then Popov notes that the shells are landing closer to them and they had better go on. Popov rides off to the right flank, and Klichkov heads toward the rear. Shells fall at the exact spot where Popov and Klichkov had stopped.

Frightened and filled with shame, Klichkov loiters around the baggage train in the rear for an hour and a half. He asks pointless questions of the cart drivers, who answer abruptly and rudely. "The minutes crawled sluggishly by, eating into Klichkov's heart like poisonous worms, gnawing at it and riddling it as though taking vengeance on him for his cowardice and shame."

All this time, Chapaev is galloping back and forth along the front lines, giving needed orders. The Cossack cavalry charges on the left flank, but they are beaten back. The Reds slowly advance and overrun the Cossack machine-gun emplacements. They raise a hurrah as they occupy the village.

All this time, Chapaev is galloping back and forth along the front lines, giving needed orders. The Cossack cavalry charges on the left flank, but they are beaten back. The Reds slowly advance and overrun the Cossack machine-gun emplacements. They raise a hurrah as they occupy the village.Klichkov, in the rear, hears the fighting end, but he doesn't know if that means the Reds or Whites won. Crushed by the consciouness of his cowardice, he skulks into the liberated village. He finds Chapaev at the newly established headquarters. Yozhikov is there, too. He smirks, as if knowing that Klichkov was hiding.

Peasant women come to complain that the Red Army soldiers are looting. Some of the looting was senseless--taking diapers and a baby carriage. Chapaev gives the men one chance to turn in all the stolen loot. After that, anyone caught with stolen property will be arrested. He says the stolen property will be returned to the rightful owners, unless of course they're bourgeois, in which case the property will go into the regimental fund.

Chapaev gathers the troops to speak to them. Klichkov finds Chapaev to be a demogogical orator, with a rambling style, staying whatever pops into his head. Workers woud be puzzled and laugh at this speech; but with the peasants, it was a great success. He tells the soldiers that if he catches anyone stealing, he'll shoot him. He condemns priests and religion, but tells the troops not to persecute or harrass believers.

When he discusses economics, Chapaev deviates somewhat from orthodox Marxism, saying, "If we take a hundred cows away from some bourgeois, we'll divide them all up among a hundred peasants--a cow to a peasant. If we take away clothes--we'll divide them the same way."

Chapaev then introduces Klichkov, who speaks on a few topics, including Chapaev's concept of giving 100 cows to 100 peasants. He "explained" the idea in such a way that he seemed to be agreeing with it, but was really demolishing Chapaev's anarchistic economic theories.

Klichkov asks Yozhikov whether he thinks they should set up a village Revolutionary Soviet right away or not. Yozhikov mutters something noncommittally and moves off. Klichkov decides to act on his own, and summons the peasants for an organizational meeting. When Yozhikov hears of this, he comes running. (What Klichkov didn't know was that Yozhikov had planned to organize the Soviet by himself and offer this as proof of Klichkov's inactivity and unsuitability for the job.)

The troops stay in Slomikhinskaya for four days. Then Chapaev and Klichkov are recalled to Samara for discussions with Frunze.

ON THE ROAD

Chapaev was a hothead, quick to blow up and berate someone, but just as quick to make peace with those he deemed worthy. He was conscious and proud of his reputation, and he himself would embroider a little on the tales of his exploits. He also had a weakness for rumors, often believing the most absurd gossip. He believed that at Army Headquarters, it was one continuous drunken orgy day and night and that it was infested with White Guardists, who took every chance to sabotage and betray the Red Army. He believed that typhus is spread by birds and that sugar grows in loaves.

On the other hand, he never believed in the possibility of defeat. Nor did he believe in the international workers movement, considering it just a fiction created by Soviet reporters to make the fighting more fun.

He had been a member of the Party for a year, but had never read and had absolutely no understanding of the Party programme. Klichkov knew he would first have to win Chapaev's trust, and only then could he educate him politically.

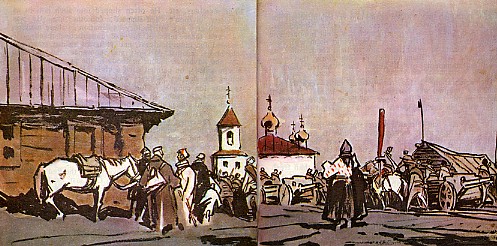

On their way to Samara, in every village Klichkov and Chapaev stopped, peasants immediately gathered to see Chapaev. They begged Chapaev to make a speech, and he would oblige. His speaches were mainly general platitutdes about the Revolution; but this satisfied the people because sometimes commonplace words of an outstanding and famous man carry more weight than an undeniably wise comment of the colorless and inconspicuous ordinary person.

During the journey, Chapaev tells his life story to Klichkov. Chapaev says his mother was the daughter of the governor of Kazan and his father was a Gypsy actor. The Gypsy ran off, and Chapaev's mother died during childbirth. The governor's family wanted nothing to do with the boy, so they handed him off to some peasant family. At age nine, Chapaev went to work herding pigs and cows. He spent time in a carpenter shop and with a grain merchant, where he learned that merchants only live by cheating.

When he was 17, Chapaev bought a barrel-organ and, with his girlfriend, Nastya, travelled up and down the Volga. To earn money, he would sing and play the organ while Nastya danced. These were happy times for Chapaev, but it ended when Nastya died.

Some time after this, Chapaev was drafted into the army. He got married and was sent off to fight the Germans. When he returned home on leave, he discovered that his wife had been carrying on with other men; so, he sent her packing. Back at the front, Chapaev began to fight with wild abandon. He was wounded several times and awarded the St. George's Cross four times.

Chapaev finally learned to read, and when the Revolution came, he decided to get involved in some parties. He played the field, joining in with the Cadets, the Socialist-Revolutionaries, and the Anachists before finally settling on the Bolsheviks.

Klichkov and Chapaev finally arrive in Samara. In private, Frunze asks Klichkov for his opinion of Chapaev. Klichkov says Chapaev's a great fighter and leader, but politically immature. Frunze agrees with this opinion, but nonetheless appoints Chapaev as a divisional commander and tells him to go to Uralsk to await further orders.

On the road to Uralsk, Klichkov and Chapaev continue their talks. Chapaev curses the "damned colonels" at Headquarters and the revolutionary military councils, which he says don't understand anything. Klichkov sees that Chapaev, in fact, knows nothing about the revolutionary military councils, and so explains them. Chapaev listens attentively. Chapaev decides that he wants Klichkov to teach him as much as possible when time permits. He even wants to study algebra.

Klichkov is astounded when Chapaev crosses himself. Chapaev says when he was a little boy, he stole some kopecks from a plate in front of a church icon. Immediately thereafter, he got sick and wasn't cured until his foster-mother put enough money back in the icon plate. Klichkov, however, patiently explains about the history of religion and God. Chapaev is convinced and never crosses himself again.

AGAINST KOLCHAK

AGAINST KOLCHAKThe Reds suffer a major, unexpected defeat on the Uralsk Front. A commission is established to find out what went wrong. Chapaev is appointed to the commission along with Klichkov, who is made chairman. Chapaev is urked that he isn't the chairman. Chapaev has his analysis of what went wrong with the attack typed up. Klichkov wants to review it for possible changes. Chapaev stubbornly refuses to make any changes and says that Klichkov can write up his own damned report. Chapaev rails against all the "damned staffs" as a horde of parasites, cowards, caraeerists, and scum. He didn't attend any academies, Chapaev says, but he gets results; and he says he is a better strategist than any of them. Klichkov bluntly tells Chapaev that he is a good fighter, but rotten in military strategy. This enrages Chapaev; he and Klichkov exchange angry words.

That night, Chapaev gives Klichkov a formal note, saying that he didn't mean to offend Klichkov and, to avoid further disputes, he offers his resignation. Klichkov, of course, smiles and rejects the idea. The very next day they are ordered to drop the business of the commission and get to Buzuluk immediately.

Chapaev's division, the 25th, is to be entrusted with the task of striking Kolchak's forces in the center and, flanked with other divisions, to drive him away from the Volga, Ufa being the immediate objective. The railway stations bustled with activity as troops poured in to join the offensive, which was to begin on April 28th.

|

|

Chapaev meets with the 22-year-old Yelan, one of the brigade commanders, who is as bold, impetuous, and dashing as Chapaev himself. In fact, Yelan is a bit jealous of Chapaev's glory. But still the men maintained friendly relations. They discuss the upcoming offensive, then Chapaev goes to address the troops. He gives one of his usual speeches--empty but crowd-pleasing.

After the speeches, an accordianist jumps up onto the stage and plays the Kamarinskaya. Naturally, Chapaev dances, which delights the troops. A dancing competion begins, followed by story-telling and singing. A good time is had by all.

When Klichkov first appeared at the Divisional Political Department, he was treated in a cool, unfriendly fashion. This arose from the fact that the political workers had a hostile attitude to the "partisan and bully" Chapaev; and this prejudice they naturally transferred to Chapaev's commissar. This hostility, however, soon melted away when Klichkov's skill, knowledge, and simplicity of character became apparent.

The offensive was launched just as the ice in the rivers began to break and the snow on the ground began to melt. The difficult road conditions contributed to the slow pace of advance initially. But as soon as they were struck, Kolchak's forces began to hesitate. The Taras Shevchenko regiment defected to the Soviet side. The initiative passed to the Red Army, and hopes soared.

MARCHING ON BUGURUSLAN

Near Buguruslan, Yelan and some 70 mounted men penetrateto the enemy's rear. A White artillery battery opens fire on them. Yelan sees that some of the White soldiers were refusing to fire on the Reds, and were being beaten by their officers in retaliation. Yelan creates a diversion, and with only a handful of men he rushes up and captures the battery. The White officers are all executed on the spot, but the Reds don't touch the ordinary soldiers.

Yelan then swoops down, captures the enemy baggage train, and redirects it back to Red lines. Not satisfied with his success, Yelan presses on toward White Divisional Headquarters. He makes an attempt to capture the White Commander, but Yelan himself is almost shot and has to high-tail it back to Red lines.

The capture of the baggage train is great success for the barefoot and ragged Reds. As a rule, regiments, brigades, and divisions always kept whatever spoils they might seize, and never reported this fact to headquarters, or even to Chapaev. As a result, the troops always had more guns and artillery then officially listed. Chapaev was aware of this deceptive practice and, when making plans, he always made mental adjustments to the figures presented to him by his commanders.

Chapaev and Klichkov make it over to Mikhailov's regiment on the Borovka River. Whites and Reds are continuously exchanging gunfire across the narrow river. Yet, strangely, while bullets are whizzing by, girls in bright Easter holiday dresses are walking around the village, singing and having a good time. The boys are hovering around them, and one is even playing the accordion. Fortunately, the Whites are only shooting at soldiers, so there are no casualties among the merry-makers.

Some Red soldiers, camouflaged, crawl down to the edge of the river and shout propaganda across to their White counterparts: "Kill your officers! They're your enemies! We're your brothers!" And the work has effect; some White soldiers shout out questions and tell the agitators how hard it is to desert.

That night, Mikhailov takes 200 men across the river for a raid on White positions. In the morning, he sends a note to Chapaev telling of success, saying he captured 150 Whites. Chapaev is dismayed that Mikhailov neglected to say how many he killed; so Chapaev just makes up the figure of 200 for the report back to headquarters. Klichkov is aghast at this invention and makes Chapaev remove it from the report.

THE BATTLE OF PILYUGINO

At the break of dawn, Chapaev's troops set out on an operation to dislodge the Whites from Pilyugino. As the early-morning artillery booms, Chapaev, Klichkov, and some soldiers move into the tiny village of Skobelevo to wait. The peasants watch the soldiers wearily. They groan, "Whites today, Reds tomorrow. Then again Whites, and once more Reds, and no end in sight. They've taken our grain, driven off our horses and cattle. They've ruined us completely." Seeing little difference between the two sides, all the peasants want is to be left in peace. Klichkov does propaganda work, explaining the difference between the Kolchak gentry and Soviet power. The peasants seem to understand and agree, but it is evident that this is all new to them.

Chapaev and Klichkov ask a woman for some milk and bread and they pay her for it. She comments that at least the Reds pay (usually), whereas the Whites never do. The Whites even abducted her son to serve with them.

While Klichkov is standing on a hill, a woman runs up to him and serruptitiously give him an egg. She wants to help because her brother is in the Red Army.

As the Reds move forward, Klichkov is in the skirmish line with the troops. Among them are friends from the Ivanovo detachment. But in the circumstances, there is no time to talk. They creep cautiously up to the village. They expect machine gun fire to bear down on them from some barns at the edge of the village at any moment; but it never materializes. The Whites abandon the village without much of a fight.

The village inhabitants--exclusively women, children and old men--wearily emerge from their cellars when they see the fighting is over. About 30 White soldiers--drafted peasants--remain in the village, saying they deserted and want to come over to the Reds. They tell how the White officers always put them in the front lines as a type of human shield, never caring if they got killed or not.

At the top of a hill on the other side of the village, two Red units open fire on each other, mistakenly, of course. Two die, five are wounded in the incident.

|

|

A White airplane flies overhead and drops a few bombs, which do no real damage.

The road to Buguruslan was now open and it is soon taken. As with most battles in this war, there was no fighting in the town itself. The decisive battle was fought on the approaches to the town, and the defenders abandoned the city to the victors.

ON THE MARCH TO BELEBEI

The Chapaev Division pushed on so rapidly, that the other units, lagging behind, were disrupting the general plan with their tardiness. Chapaev was the perfect leader for this group of men at this particular time. With his denunciations of all "staffs" and glorification of the soldier in arms, Chapaev inspired his troops to endure impossible conditions and to honor the tradition of never surrendering. "How magnificent this was, but how fallacious, harmful and dangerous!" His unit included two one-legged soldiers who continued to fight with the regiment as machine-gunners.

As Chapaev's fame spread, he often received appeals, such as one from a functionary in Novouzensk, begging Chapaev to come and give what-for to some thieves, "spiders and microbes", who were plaguing his life. Chapaev would quite willingly interfere in such matters, the the time pressures of war did not often permit it.

|

|

A few days later, Yelan receives an order from Chapaev to smash the enemy, but leave the mopping up to another brigade. This angers Yelan, who wants to get revenge for the men he's lost. Yelan ignores Chapaev's direction and orders his men to pursue the fleeing enemy for 15 versts. When Chapaev hears of this, he flies into a rage. He and Yelan yell and scream at each other and almost get into a shooting duel. Messengers are sent to countermand Yelan's order. They calm down and eat a chicken. Chapaev rethinks and orders that more messengers be sent out to stop the first messangers and leave Yelan's order in effect.

The hills are captured, and Yelan gets Chapaev's silver sword. Yelan gives Chapaev his own sword in exchange.

When the 220th Regiment takes Trifonovka, they discover two horribly mutilated corpses under a pile of manure. The peasants describe what happened. While the village was still controlled by the Whites, two Red Army cooks blundered in. The Cossacks grabbed them and questioned them. Then the Cossacks were seized by a wild, insane, bloodthirsty fury. They savagely beat and kicked the prisoners. They ripped strips of flesh from their bodies and rubbed salt in the wounds. They stabbed the Reds, but not too much so they wouldn't die too soon. Then, when evacuating the town, they hid the bodies under the manure. This discovery had a profoundly moving effect on the Red soldiers. Despite Klickhov's speeches about not seeking vengeance, there was not one prisoner taken during the next day's fighting.

On another operation, Yelan captures a large group of prisoners. In among them, Klichkov spots one that is well-fed--obviously an officer trying to pass himself off as a common soldier. When the officer is exposed, he is haughty, arrogant, and insolent. Klichkov orders him to be shot--the first time Klichkov gave out a death sentence. Klichkov was bothered by this for a day or so, but soon forgot about it. Chapaev and other battle-hardened veterans all agree that the first time is difficult for everyone, but soon you get used to killing.

Yelan tells the story of his orderly, Stepkin, who, in one village, raped a woman. Although Yelan felt sorry for Stepkin, he ordered that he be shot. When she heard about this, the woman--although she had indeed been raped--quickly changed her story. She and Stepkin went through a sham marriage, and the next day Stepkin marched off and never saw her again. Since then, Stepkin has proven to be quite a hero in battle. Chapaev feels that a soldier should be able to spend two or three years at the front without a woman.

Chapaev and Klichkov ride on to Shmarin's brigade. Shmarin was a competent leader, who could follow orders well, but he was weak in independent thinking. He also was a braggard, who loved telling how he was the hero of every battle, even though this rarely bore any resemblance to the truth. This was a not uncommon trait among commanders.

Chapaev walks along behind the trenches. No one shoots at him, and this makes him suspicious. Scouts are sent up to the top of the ridge where they discover that the Whites are gone. Shmarin says they probably ran away because they feared his battle prowess. Chapaev, however, after surveying the situation concludes that the White are moving around to attack in the rear. Chapaev orders just the right countermeasures which foil this ploy.

That night, all is quiet at Headquarters. Shmarin gallops up and raises the alarm, the Whites are attacking! Everyone jumps up quickly and rushes forward, ready for battle. There is confusion in the ranks. But it turns out to be a false alarm--the "enemy" is just some Red soldiers on the hill. Chapaev asks Shmarin who first raised the alarm; Shmarin says he doesn't know; it was just some fellow who raced by him shouting. Chapaev says it's important to alway "know". He relates an incident from his experience in World War I. Russian troops, complete with oxen and horses, were moving up an Austrian hill in the pitch black of the night. Someone got scared and started shooting into the black. Everyone took panic and started shooting at everyone else; the oxen and horses stampeded; and there were many casualties.

FORWARD

The Reds move on to take Belebei. Chapaev's division is ordered to halt on the banks of the Usen River. This delay enfuriates Chapaev, who wants to continue the attack immediately. Klichkov tries to reason with him, saying that they must coordinate their efforts with the rest of the army. Chapaev insists that the men don't need any rest. He says that in the woods he met up with an wounded Red Army man who, not giving his wound time to heal, was hobbling back to his unit because he was needed there. "If they kill me, I'll lie in my grave and my wound will have time to heal there," he said. Chapaev was greatly moved by the enthusiasm of this hero and gave him his wristwatch as a gift.

The Red Army men tell Klichkov that there is a 19-year-old girl traveling along with the baggage train, wanting to go to Ufa with them. Although everything appears normal with the girl, Klichkov is for some reason suspicious. Through some clever questioning, Klichkov forces the girl to admit that she is a Kolchak spy! She had White identification papers, printed on extraordinarily thin paper, hidden in a cigarette holder. She was sent to sent to Army Headquarters and even questioned by Frunze himself. She revealed much useful information, including the names of some double-agents among the Red. The double-agents were "eliminated".

As the Red Army moved toward Chisma, the fighting became more intense and almost constant. But despite this, the Kolchak forces gave the impression of a little dog fleeing a much bigger dog, trying to bite back, but knowing that it cannot win. Two factors helped accelerate the demoralization of the Kolchak forces. Firstly, the heterogeneity of the troops; Kolchak had conducted his mobilization among the populace indiscriminately, caring only about numbers, not quality. And secondly, Kolchak gave his officers free reign in meting out reprisals among their own army. All the old abuses in treatment of the soldiers were resurrected.

|

|

In the end, the Reds take the town, and the peasants were soon bustling about, feeding the troops and serving them tea. That evening, there is singing and dancing until late into the night. The soldiers even have a half-serious, half-comic churchlike chant calling for blessings for Lenin, the Red Army, and all artillery men, cavalry men, infantry men, cooks, etc., etc. The chant also prayed for the bestowal of eternal peace in blessed sleep on Kolchak, his worshippers, hangers-on, toadies, Czechoslovakian gentlemen, counterrevolutionaries, careerists, monarchists, speculators, wreckers, etc., etc.

Decorations are sent out for the victory at Chisma. In several regiments the awards are refused on the grounds that everyone deserved and earned them and that no individuals should be singled out for praise. Klichkov and all the political workers send a protest to the Central Committee about the while idea of decorations.

|

|

Solving the "women question" in the army was difficult. An order came down to remove all wives and women in general. The flock of wives and family following the troops was enormous and caused many logistical problems. And the women led to fights and distractions among the men. But what about the women nurses, doctors, and political workers who were so necessary? Klichkov personally intervened on behalf of and won the reinstatement of several women weaver-soldiers who were being turned out of their regiment.

UFA

The Whites fortified themselves on the heights of Ufa, while the Reds gathered opposite on the other side of the Belaya River. Two steamboats and a tug filled mainly with White soldiers and officers are sailing leisurely along the river, apparently unaware that Reds are near. The Red open fire and capture the boats. The White officers either shoot themselves or jump overboard to avoid capture.

In the pitch black of night, the Ivanovo-Voznesensk regiment is ferried across the river to the Ufa side. As dawn approaches, the Red battalions in Krasnaya Yar open fire on the White trenches, forcing the Whites to fall back in panic. The Ivanovo-Voznesensk regiment pushes rapidly forward and establish themselves in the settlement of Noviye Turbasli. The Whites mount a counterattack, and the Ivanovo-Voznesensk troops, who have almost completely run out of ammunition, start to waver. Just then up rides Frunze himself, who grabs a rifle and charges forward, shouting. This fills the troops with wild enthusiasm, and the enemy is repulsed. More ammunition arrives and the Ivanovo-Voznesensk troops continue on to Stariye Turbasli.

Frunze's horse is shot out from underneath him and he is rattled by an exploding shell; yet he keeps on supervising the unloading of fresh troops on the river bank.

On the Krasnaya Yar side of the river, Chapaev is sending more regiments across on the ferries. He sees that on the Ufa side, some Red troops are retreating and crowding on the bank. He urgently sends Mikhailov across to establish order. Mikhailov rallies the troops, threatening to shoot anyone who retreats.

Chapaev is in excellent communication with the forward troops and gives all the needed orders. He is very vexed, breathing thunder and lightening, over the White airplanes, which are bombing and strafing the river bank. In fact, an airplane fires down and...Chapaev is wounded! A bullet hits him in the head and is lodged in the bone. The bullet is removed, his wound tended to, and his is evacuated to Avdon. Temporary command passes to Yelan.

In the evening, a worker who has snuck out of Ufa informs the Reds that some White officer battalions are planning a sneak attack on Red positions in the morning. Thanks to this information, the Reds are ready. They let the enemy sneak into close range, then open fire. It is a ghastly carnage as the Whites are mowed down. The Reds advance and by the evening, they are in the outskirts of Ufa.

On the other flank, there is a bridge leading into Ufa. Strongly suspecting that the bridge is mined, the Reds sentd some workers on it to try and clear it. The Whites immediately open fired to hamper the operation. Klichkov crawls out onto the bridge and sings the Internationale. For some reason, this silences the enemy. But when Klichkov jumps up and shouts out, "Comrades!", the Whites resume fire. The Reds withdraw from the bridge. Then, for no apparent reason, the Whites blow up the bridge. The Reds immediately begin crossing the river however they could--on rafts, on logs. The Whites fire back, but seemingly disorganized, in panic.

|

|

While other divisions chase Kolchak, Chapaev's men stay in Ufa to rest. Soon they hear alarming reports of Cossack successes on the Uralsk front. The men want to return to their native territory and wide out the savage Cossack bands. The Center agrees and Chapaev's division is told to go back to the Uralsk steppes.

THE RELIEF OF URALSK

THE RELIEF OF URALSKUralsk had been encircled by the Cossacks. The garrison and workers put up a heroic defense despite the lack of ammunition, fatigue and hunger.

On the road to Uralsk the Chapaev Division encountered little resistance. But near Sobolevskaya, the Cossacks fell upon and annihilated a company of Red soldiers who had been separated from the main body of troops. The same fate befall a second and third company sent to aid the first. Finally an entire regiment was sent to smash the enemy. When learing of this episode, Chapaev flew into a towering rage.

In all the villages, Chapaev was hailed as a hero. Chapaev would lecture the peasants on the source of the Red Army's strength, its class composition, as well as the need to help the famine-stricken center. As usual, much of what Chapaev said was nonsense, but it had a constructive effect for he appealed for industriousness and protested against greed, selfishness, and ignorance. In one village, the peasants, inspired by Chapaev, promised to scrape up every last bit of grain and send it to Moscow.

After only one main battle, the Cossacks withdrew from Uralsk. Chapaev is met with joyous shouts and a brass band playing the Internationale. Klichkov has a happy reunion with Andreyev, who has been working in the city. Andreyev says that the struggle against webs of treachery and conspiracy in Uralsk had required ruthless measures.

|

|

Occasionally, Chapaev exhibited a tyrannical pigheadedness. A well-known "horse doctor" from Chapaev's native village shows up. Chapaev summons the division veterinary surgeon and his commissar. He orders them to "examine" the peasant and immediately give him a diploma as a "veterinary doctor". The surgeon and commissar explain that they don't have the right to issue such a document. Flying into his usual rage, Chapaev threatens to shoot them. They flee to Klichkov for protection. Klichkov tries to calmly reason with Chapaev, who responds, "You're all swine! Intelligentsia!" Klichkov finally gets Chapaev to agree to send a telegram to Frunze and let him decide the matter. Klichkov writes the telegram, but doesn't send it. Five minutes later, calm and having tea with Klichkov, Chapaev agrees to tear up the telegram.

FINALE

Chapaev's division pursues the Cossacks across the steppes. Here, however, all the villages are pro-Cossack. When the Reds arrive, the houses are all abandoned, grain stores destroyed, and wells poisoned. The Cossacks fight fiercely and the Red soldiers are on the verge of starvation.

Chapaev and Klichkov need to see Yelan, so they take off with an escort of 12 men. Rain pours down, it grows dark and they become lost. They decide to ride toward some flickering nocturnal lights in the distance, thinking that perhaps it is a campfire where Yelan's men are bivouacked. But no matter how far they ride, the lights never seemed to get any closer. And they feared a Cossack patrol might come upon them at any moment. They finally decide to stop for the night by some stacks of unthreashed grain. They make themselves little caves in the straw and sit there out of the rain. Klichkov, soaking wet, is miserable. However, Chapaev bursts into song.

Chapaev recounts a story of two men who were lost in the desert. One died, and the other was rescued in the nick of time by a passing caravan. Chapaev says that when he's in a tough situation, he likes to recall others who were in a worse position and survived.

Petka, one of Chapaev's most trusted men, remembers when he and other Bolsheviks were locked up in a shed by some Cossacks on the Don River in 1918. They were to be executed in the morning. But Petka managed to squeeze through a small crack in the shed and beat the guard to death with a brick, so that he and his comrades could escape.

In the morning, Chapaev and the others have little trouble catching up with Yelan in the village of Usikha. Yelan and his commissar are dirty, exhausted, hungry, and in dispair. The terrain all around is completely flat, and the Cossacks make four attacks a day. Ammunition reserves are so low that Yelan has ordered that only every tenth man is to fire. They review the plans for the next day's attack. Chapaev promises that ammunition and food are on their way.

Chapaev then rides over to Shmarin's brigade, where they actually have some food. Chapaev reviews every possibility for tomorrow's battle. Then he receives an invitation to attend a theatrical performance. Chapaev and Klichkov are suprised to hear that Zoya Petrovna is staging theatricals so close to the front. But she has been tireless and bold in bringing her performances right up to the trenches. Occasionally, Red positions were attacked during a play. The actors immediately all picked up rifles and joined the troops in battle.

|

ODE TO CHAPAEV Bringing death to man and beast Came the Bolsheviks' huge armies, Quickly marching to the east. And they had much ammunition, Many a mortar, gun, and spear, And there led them, arms akimbo, Grim Chapaev, mutineer. He'd have liked the Ural stormy, To subdue and take in hand; And the villages were burning, Bitter wailing filled the land. All the shooting, rape, and pillage, Can it ever, then be told? So the villagers held council, All the men both young and old. "There'll be sorrow, there'll be trouble, In the land we all adore, Oh, you Cossacks, take up lances, For the happy days of yore! "Send the Bolshevik invaders And their Commissars to hell. Before they came to stir up trouble Russian Cossacks lived full well. "Rise, you eagles of the steppe land, For there's jolly work that's toward. From the wall take down your rifle, Sharpen well your trusty sword!" And the Cossacks leaped to saddle, Gave the horses, then, their heads, And in solid mass formation, Hurled themselves against the Reds. While behind them Old Man Ural Watched the charge with smiling face, As the Reds ran back in terror, In the depths of their disgrace. |

After the play, an actor reads out a poem written by the White guard poet P. Astrov and dedicated to Chapaev that was found in the village. It tells of Chapaev's "atrocities" and calls on the Cossacks to trounce him. After the reading, Chapaev gets on stage and gives a colorful speech, describing some of the trouncings he's given to the Cossacks. The troops all are fired with enthusiasm and give Chapaev a festive send-off when he leaves.

This was Klichkov's last trip with Chapaev. After six months with the heroic commander, Klichkov was being recalled to the center for different work. Klichkov did not want the new assignment, and Chapaev had sent many telegrams begging that Klichkov remain with him, but all to no avail. Looking back on the last six months, Klichkov realized that he had developed greatly, had become much stronger spiritually. So tempered had he been by the ordeals he had undergone, he now proceeded simply and confidently to solve the most diverse problems, which, before his experience at the front, would have seemed infinitely difficult.

Klichkov's replacement, Baturin, arrived. Klichkov introduced him to the political staff, then held a little going-away party for himself. The political workers were genuinely sorry to see Klichkov go. They especially valued him for his ability to hold in check Chapaev and Chapaevism, that is, all those unpleasant and, at times, dangerous attacks on political workers, the Cheka, and the staffs.

The next morning, Klichkov departs for Samara. Chapaev and Baturin go to inspect the brigades and regiments. The offensive was developing successfully. Chapaev came to realize that here he could not use the same tactics as when fighting peasants forcibly mobilized into Kolchak's army. The Cossacks were brave, motivated fighters, and they were not disconcerted by the loss of territory. They would gallops boldly back and forth across the wide open steppes, their home. Nor were the Reds to expect any Cossack deserters to join them. Chapaev's main goal became the destruction of enemy manpower.

At Lbishchensk, Chapaev launched a frontal attack. The Cossacks were not expecting this, and were forced to withdraw. At Mergenyovsky, however, the Cossacks had caught on to Chapaev's new tactics and put up a spirited defense. The Red forces suffered heavy losses, but still won the battle.

|

|

Shmarin's brigade got lost in the bare, empty steppes. They ran out of food and water. There was an increase in sicknesses; there were no doctors and no medicines. The Kushum River had dried up to a greenish-brown much. They found wells filled in with dirt, and other wells filled with rotting carcasses of cows and horses. The carcasses were hauled out, and what water could be found was rationed to the thousands of parched men. For this blunder, Chapaev demanded that Shmarin be courtmartialed and shot. Yelan prevailed on Chapaev to only demote Shmarin.

With autumn approaching, the position of the retreating Cossaks was increasingly desperate. They decided to penetrate unnoticed to the rear of the Red forces and to deliver a sudden, deadly blow at Lbishchensk, where Red Divisional Headquarters were now situated.

At Headquarters, Chapaev frets about the troops at the front, suffering from lack of supplies and from typhus, which is mowing down soldiers in droves. He receives a report that a Cossack patrol attack a transport column 15 versts away. Chapaev orders that the Division School be put on sentry duty that night.

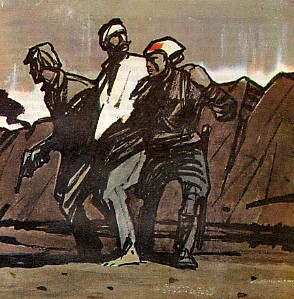

Sometime during the night, someone--no one knows who--orders the Division School off their posts. As the first hint of dawn appears in the sky, the Cossack hordes attack the unguarded and unprepared village. Red Army men, in their underwear rush out with rifles. Several dozen Reds set up a skirmish line around Chapaev, who appears with a rifle in his right hand and a revolver in his left.

All is confusion among the Reds, who are fighting in isolated groups, no one knowing what anyone else is doing. Seeing that their position is practically hopeless, Baturin leads his group of political workers in a charge on the attacking Cossacks. This charge is so unexpected that the Cossacks fall back, abandoning two machine guns, which Baturin immediately turns on the enemy.

Soon, under a fierce onslaught, Baturin has to flee. He tries to hide in a house, but the housewife gives him away to the Cossacks. Overjoyed at having nabbed a genuine commisar, the Cossacks start a bloody orgy. They run Baturin through time and again with their sabres. Then they whirl his body around and smash the skull so that his brains go flying out.

Chapaev is wounded in the arm and the head. Petka and others help him down the steep bank and into the Ural River. They start to swim across to the Bukhara side. The Cossacks rake the river with machine gun fire. Chapaev is almost across to the other side when a cruel bullet hits him in the head. Chapaev disappears in the swift waters of the Ural.

Chapaev is wounded in the arm and the head. Petka and others help him down the steep bank and into the Ural River. They start to swim across to the Bukhara side. The Cossacks rake the river with machine gun fire. Chapaev is almost across to the other side when a cruel bullet hits him in the head. Chapaev disappears in the swift waters of the Ural.Petka, who had stayed behind on the river bank, fought off the attacking Cossacks as long as he could. He put his last bullet into his own heart. The Cossacks glutted their insane rage on Petka's body, mutilating it almost beyond recognition.

The Red units holding positions at Sakharnaya were stunned when they heard of the disaster at Lbishchensk. Yelan assumes command. In the dead of night, the Reds start to pull back, hoping that the Cossacks wouldn't notice right away. They march for two days and two nights without any rest. They pass through Lbishchensk, pausing only to bury the hundreds of their comrades whose bloody corpses were still lying around.

The Reds get to the hamlet of Yanaisky and, exhausted, fall into a dead sleep. Taking advantage of this, the Cossacks mount a massive dawn attack. At first, many Red commanders are killed and there is disorder and panic in the ranks. Then Nikolai Khrebtov organizes the artillery and begins a devastating bombardment of the enemy. The Reds rally to turn defense into attack . Many Red soldiers are killed that day, but even more Cossacks are left on the field. The seemingly dead Reds once again shown what the Chapaev Division is capable of.

Soon, reinforcements arrive, and the tide is turned. The Red regiments launch an attack which does not stop until they reach the shores of the Caspian Sea.

|

|